Articles

Untitled Document

urn:nbn:de:0009-29-55428

1. Introduction*

1

Today, the exploitation of copyrights is significantly more complex than it was before the digital era. Whereas in the past responsibilities were predefined by the de jure or de facto territorial monopoly positions of collective management organisations (CMOs) in the European Union (EU), the arrangement of copyright exploitation options is more liberal today: numerous options have been manifested in law, ranging from independent management of rights by the rightholders to delegation of the management to private independent management entities (IMEs) or multiple CMOs. [1] While management responsibilities may be limited to a certain geographical area, specific “categories of rights”, “type[s] of use”, or other subject-matter, pan-European competition/specialisation and collaboration/consolidation of CMOs has increased. [2]

2

However, it is frequently argued that these trends are harmful to the system of collective rights management (CRM). The primary points of criticism lie in the fragmentation of rights that is caused: additional administrative burden arose for rightholders and CMOs, which can only be covered by economically strong rightholders or CMOs; legal uncertainties arose for licensees as to the delimited field of use to which the licenses they seek to obtain apply. [3]

3

Klobučník (2021) points out that problems of this kind may be resolved by providing a (legislative) “compass” to navigate through the landscape of the CMO (online licensing) market. As such it is not the complexity of the system per se, but the lack of its transparency that leads to aforementioned problems. [4]

4

The transparency of CMOs can be evaluated from both a legislative and a practical perspective. Compared to previous legislation, Directive 2014/26/EU introduced a number of provisions that should have contributed to more transparency in the activities of CMOs.

5

CMOs are now required to publish information about their internal and external business structure, membership terms and user tariffs, policies regarding royalty distributions, associated administrative fees and cultural deductions, and procedures for handling complaints and resolving disputes. [5]

6

From a practical perspective, Hviid et al. (2017) evaluated the availability of public information of four CMOs for musical-repertoire for the aspect of multi-territorial licenses for traditional broadcasting and web streaming. It was found that the information is vague and unstructured, only partially available in English, and therefore difficult to understand for a broad readership, leading to legal uncertainty and high search costs for potential licensees to find out what repertoire they can use and what rights for which territories are granted. [6] These findings indicate a lack of transparency on the licensing activities of CMOs, which is also relevant for rightholders considering entrusting CMOs with the administration of their rights.

7

In addition to public information on their websites, CMOs are obliged to publish annual transparency reports. [7] The mandatory contents of the transparency reports are defined in the Annex of the Directive 2014/26/EU. Among others, these are information regarding business structure and finance, which are particularly relevant for rightholders interested in transferring their rights for administration. As specified in the Directive, the financial information published in the transparency reports must include, inter alia, statements on royalty income collected by CMOs during the fiscal year, administrative and financial expenses, deductions for social, cultural and educational services, and the amounts of royalties distributable and distributed to rightholders and other CMOs, each broken down by “categories of rights” and “type[s] of use”. [8] The financial information should be reviewed by at least one qualified reviewer according to the criteria set out by Directive 2006/43/EC. [9] While this ensures that the transparency reports are valid according to general criteria, their evaluability is nevertheless limited.

8

Neither Directive 2006/43/EC nor Directive 2014/26/EU specify exactly the semantics of “categories of rights” and “type[s] of use” [10], or what criteria should be used to classify them. This leaves CMOs a great deal of latitude in presenting information on these subjects of representation. Yet, this information must be comparable across CMOs in order to promote competition. [11] Closely related to this are the questions how and which rights are transferred by rightholders to CMOs and which types of use are thus licensed to licensees. This two-sidedness of rights management by CMOs is sometimes expressed by referring to the assignment of rights by rightholders to CMOs as the “upstream” phase and the licensing of rights by CMOs to licensees as the “downstream” phase. Thus, CMOs compete in two markets: for rightholders and for licensees of their repertoire. [12]

9

Unless otherwise provided by law or the statutes of a CMO, its general assembly of members shall determine which categories of rights, types of use and other subject-matter are to be managed. [13] In several EU countries, the transfer of rights is to be made “in dubio pro auctore”. In this respect, the transfer of rights is limited to those rights that are expressly set out in the authorisation contract. [14] While certain relaxations of this rule apply in some countries [15], the problem stays the same at its core: The protection of rights by CMOs in this case does not apply to types of use that were not foreseeable at the time of the conclusion of the contract. [16] Yet, whether or not a use can be attributed to specific transferred rights stays a matter of interpretation. To minimise variance, legal uncertainty and thus to ease copyright enforcement, publishers and CMOs usually apply standard contracts, having broad right bundles to be assigned by default. However, this limits the decision-making room of rightholders as to which rights can be transferred. [17]

10

As blurred as the transfer of rights is in the upstream phase (from the rightholder to the CMO), as blurred it is in the downstream phase (from the CMO to the licensee). This becomes apparent, for example, in the case of tariff comparisons between CMOs: The transferred rights form the basis, while further, exploitation-specific parameters fine-tune the calculation of rates. [18] However, case law showed that the scope of the rights transferred for the use and the additional parameters used for the calculation of the tariffs were blurred to a degree where it was unclear whether the tariff charged by the CMO is actually fair. Thus, the comparability of CMO-tariffs is limited and multi-territorial competition of European CMOs can hardly be objectively disputed. [19]

11

Given that individual modular right-assignments are now supported by law and the conditions for multi-territorial licensing practices are considerably harmonised, the transparency on right-assignments seems even more important than in the past.

12

For these reasons, we examined in detail how categories of rights and types of use are reported in the transparency reports of 21 CMOs for copyrights in musical works according to different evaluation criteria. In order to refer to these terms simultaneously, we summarise information reported on these under the label “license categories” [20] . We conclude our analysis by identifying problems in terminological inconsistencies, language, presentation and structure of the reported information. It is shown, that a comparative assessment of the information is only possible with laborious, biased and inaccurate human interpretation, which raises the question of whether transparency reports in their current form are even a meaningful resource for rightholders to use in market analysis when comparing the performance of different CMOs. Conversely, we also find that many of the problems are avoidable if CMOs would use a consistent terminology. Thus, we propose the introduction of controlled vocabularies and therefore suggest a taxonomy and an ontology of collective license categories. In addition to the potential these artefacts may offer, we highlight their limitations and discuss further steps to enforce comparability of the investigated subject-matter.

2. Methodology: Assessing transparency reports of CMOs for music copyrights

13

To investigate whether CMOs have a common denominator on how they report details on “license categories” [21], we analysed the transparency reports of European CMOs managing music copyrights. To obtain our sample, we accessed the official list of CMOs published by the EU Commission. [22] At the time the study was conducted (November-December 2020) this list categorised CMOs by their residence in an EU member state. The list was not organised according to any other criteria such as the repertoire or the rights represented by the listed CMOs. In order to identify the CMOs representing music copyrights, we compared the listed CMOs with the member directories of CISAC [23], the largest international umbrella organisation of collecting societies [24] for author rights, and BIEM [25], the international umbrella organisation of collecting societies for mechanical recording and reproduction rights. The member directory of the CISAC provided the possibility to filter collecting societies based on different options, including the represented repertoire and their country of residence. As in our case collecting societies for music copyrights in EU countries were to be examined, we filtered accordingly. No such option was offered by BIEM, whose members also included societies for mechanical reproduction rights in literary and dramatic works. Thus, if collecting societies were members of BIEM but not included in the CISAC sample, their repertoire was cross-checked through their respective official websites.

14

Only 19 out of the 31 sampled CISAC collecting societies were officially declared as CMOs by the EU member states. In the case of BIEM, these were 17 out of 26. Only three BIEM collecting societies were not already among the 19 CISAC member societies, and one of the three BIEM CMOs was not an officially declared CMO of the EU. Thus, the final list comprises 21 CMOs. For the selected CMOs, transparency reports for the financial year 2019 were collected from their respective public websites. We noted that two CMOs had not published a transparency report for the relevant year on their website during the survey period, so these CMOs were excluded from further consideration, resulting in a sample size of 19 CMOs.

15

We reviewed the disclosure of financial information on license categories [26] in the transparency reports using uniform criteria, as described in Table 1.

Table 1: Criteria for the quantitative analysis of transparency reports

|

Identifier / Label |

Description |

|

Q1. number of reported categories of rights |

The total number of reported categories of rights. In the absence of a legal definition of categories of rights, we define inductively that these comprise all classes of licensed rights reported by a CMO at the top level of aggregation.In this context, aggregation means the grouping of license types with common attributes and cumulating their revenues. Other revenue sources such as financial instruments are also not counted as categories of rights. |

|

Q2. number of reported residual classes of categories of rights |

The total number of reported categories of rights that do not fit into the report's classification scheme, e.g., ‘other’, ‘miscellaneous’, or those categories of rights that are not actual aggregations of licensed rights, but are licensing modalities such as ‘central licensing’. |

|

Q3. number of reported types of use |

The total number of types of use reported. In the absence of a legal definition of types of use, we define inductively that these comprise all classes of licensed rights reported by a CMO at the lower levels of aggregation, which are elements of categories of rights whose subtotals add up to the total of a category of rights. If more than two hierarchy levels were reported, the classes on the lower hierarchy level are counted as additional types of use. |

|

Q4. number of reported residual classes of types of use |

The total number of reported types of use that do not fit into the report's classification scheme, e.g., ‘other’, ‘miscellaneous’, or those types of use that are not actual aggregations of licensed rights, but are licensing modalities such as ‘central licensing’. |

|

Q5. number of reported classes of rights for payments to other CMOs per CMO |

The number of classes of rights at the finest reported level of aggregation for which amounts for payments to other CMOs per CMO were reported: i.e., the number of types of use when categories of rights and types of use were reported, since the reported amounts for the types of use are subtotals of the categories of rights they contain. |

|

Q6. number of reported classes of rights for payments from other CMOs per CMO |

The number of classes of rights at the finest reported level of aggregation for which amounts for payments from other CMOs per CMO were reported: i.e., the number of types of use when categories of rights and types of use were reported, since the reported amounts for the types of use are subtotals of the categories of rights they contain. |

16

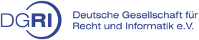

Figure 1 illustrates the introduced concepts and their interrelations by example. We refer to the criteria by the introduced identifiers.

Figure 1: Illustration of the abstract concepts described in Table 1

17

While the first set of criteria (Table 1) was designed to quantify the heterogeneity in the way CMOs report information on categories of rights/types of use, the second set of criteria (Table 2) was compiled to identify qualitative differences.

Table 2: Scheme for the qualitative analysis of transparency reports

|

Identifier / Label |

Description |

Scale |

|

E1. separation by managed repertoire |

If the CMO manages other repertoire types in addition to musical repertoire, the separation of financial information should be apparent to them. |

0 = information on repertoire types is inherently mixed; 1 = information can be separated most of the time; 2 = separation is unambiguously clear |

|

E2. separation of performing and mechanical rights |

In music copyrights the CISAC differentiates between ‘performing rights’ and ‘mechanical rights’ (CISAC, 2020a). The classification of license types into one of these two broad right categories might provide a first starting point to differentiate information on business figures. |

0 = reported categories of rights and types of use do not allow for a binary mapping to performance or mechanical rights; 1 = some categories of rights or types of use do not allow for a binary mapping to performance or mechanical rights; 2 = most or all categories of rights and types of use are explicitly mapped to either performance or mechanical rights |

|

E3. separation by usage specifics

|

The standard tariffs for granted performance rights or mechanical rights depend largely on the specifics of their use (Ficsor, 2005), i.e. where the usage takes place (e.g. broadcast, online, live). |

0 = information is not separated by specifics 1 = separated by specifics for the most cases 2 = by specifics for all the cases excluding residual categories |

|

E4. consistent vocabulary

|

The vocabulary for the categories of rights and types of use should be consistent throughout the report, i.e., there should be only one label per term. |

0 = most terms have multiple labels 1 = some terms have multiple labels 2 = the vocabulary is consistent throughout the report |

|

E5. cohesive categorization

|

There should be a fixed classification scheme to which the CMO adheres in reporting that is comprehensible, i.e., the criteria for consolidating the individual classes of rights should be consistent throughout the report. |

0 = no classification scheme is recognisable at all 1 = the classification scheme is partially blurred 2 = the classification scheme is clear and distinct |

3. Findings: heterogeneous terminology and aggregation structure

18

According to the Annex of Directive 2014/26/EU, CMOs are required to list amounts for the categories of rights/types of use they manage in different sections (collections, distributions, payments, etc.) of the transparency report. We found that CMOs reported on average 9.79 categories of rights (Q1), with values ranging from 3 to 25, across all sections (see Table 3). The CMOs reporting a small number of categories of rights were strongly oriented towards the common differentiation between performing rights and mechanical rights, which they treated as major categories of rights. As a median, CMOs reported only one residual category (Q2). Only 9 of the CMOs surveyed reported amounts for specific types of use in addition to amounts for categories of rights. For these CMOs, the number of types of use (Q3) reported ranged from 8 to 50, with a median of 20.56. When CMOs reported types of use, the median number of residual types reported was two (Q4).

Table 3: Raw data of the quantitative survey [27]

|

CMO Q |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

|

1 |

19 |

4 |

15 |

12 |

4 |

10 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

8 |

25 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

13 |

12 |

8 |

15 |

|

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

4 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

6 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

- |

|

3 |

- |

10 |

- |

- |

8 |

- |

21 |

14 |

- |

19 |

- |

- |

- |

29 |

19 |

- |

- |

15 |

50 |

|

4 |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

2 |

|

5 |

? |

8 |

12 |

9 |

- |

- |

13 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

10 |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

|

6 |

? |

8 |

12 |

8 |

- |

- |

3 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

- |

8 |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

19

These figures do not necessarily indicate the range of categories of rights/types of use managed by a CMO, but rather the different approaches of an aggregated reporting. The more CMOs aggregate royalty revenues or payouts, the more difficult it is to compare the composition of these amounts with those of other CMOs. A possible reason for this heterogeneity may result from the vague description of the requirements in Directive 2014/26/EU and the resulting scope of interpretation for their implementation by national legislators. To illustrate this issue by an example, consider point 2.d.i of the Annex to the Directive:

“(d) information on relationships with other collective management organisations, with a description of at least the following items: (i) amounts received from other collective management organisations and amounts paid to other collective management organisations, with a breakdown per category of rights, per type of use and per organisation;”

20

This sentence can be interpreted in multiple ways: on the one hand, it could mean that the amounts received and paid out are to be disclosed by categories of rights and types of use for each cooperating CMO, but on the other hand, it could also mean that the amounts from representation agreements are to be disclosed by categories of rights, types of use and CMOs as separate items. When the Directive was implemented by the German legislative, this ambiguity was unravelled and the first interpretation just described was manifested in the Annex to Section 58(2) of the VGG [28]:

“d) Information on relationships with other collecting societies, in particular: (aa) amounts received from or paid to other collecting societies, broken down by category of rights managed and type of use for each society;”

21

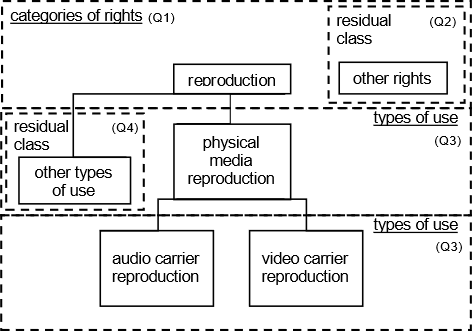

However, it cannot be assumed that every national legislator follows this interpretation. Therefore, it is not surprising that not all of the surveyed CMOs reported the amounts per CMO broken down by categories of rights and types of use: eight CMOs did not report the amounts per cooperating CMO or only the total amounts under the representation agreements (Q5, Q6). Of course, such problems do not necessarily have to result from the lack of a clearly defined reporting scheme in every case, but can also be due to organisational problems on the part of the reporting CMO. [29] In general, however, those CMOs that produce reports on a more fine-granular level allow readers of the transparency reports to gain deeper economic insights. Figure 2 summarises the quantitative findings in graphical form.

Figure 2: Boxplots for the quantitative findings

22

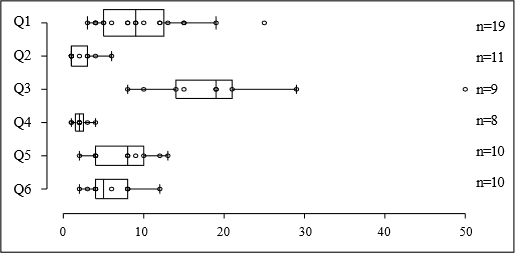

While the previous explanations have dealt with the differences in transparency reports on a quantitative rather than a qualitative level, the following paragraphs assess various qualitative aspects of the reports (see Figure 3 for a graphical summary).

Figure 3: Summary of the qualitative analysis of the reports

23

If a CMO manages multiple repertoire types, the distinction between the business figures reported for these particular repertoires should be clear (E1). While this distinction is required for the granting of rightholders’ authorisations to CMOs (Article 5) and for certain requests for information (Article 20), it is not made explicit in Directive 2014/26/EU for transparency reporting. In the investigated sample, four of the CMOs also managed royalties for other types of works in addition to musical repertoire. Two CMOs reported the business figures required by the Annex to the Directive entirely and explicitly separated by repertoire types, one at least in several instances, and one CMO did not break them down at all. This particular CMO licensed only music repertoire, but served as an intermediary for domestic CMOs with other types of repertoire, to which it forwarded payments in categories of rights or types using the same designations, making it impossible to track what repertoire was covered by the reported indications. However, this type of differentiation is not explicitly required in the annual transparency reports according to Directive 2014/26/EU.

24

In addition to the differentiation of figures for repertoire types, the distinction of amounts for performing rights and mechanical rights (E2) is also of interest for rightholders and licensees, for example, in order to estimate the administrative costs of the CMO for the respective rights. Among the CMOs examined, eleven managed both mechanical and performing rights, for which such a distinction is relevant at all. Four of them fully and explicitly assigned the reported categories of rights/types of use to one of these broad categories of rights. Six of the analysed CMOs assigned at least some of the reported amounts to either performance rights, mechanical rights, or statutory rights, or the assignment was implicitly apparent. One CMO used the same labels for categories of copyrights as for related rights, blurring the indications.

25

A special case and excluded from this analysis is the NCB, a CMO that manages not only mechanical rights but also synchronisation rights. These type of rights are usually not negotiated with licensees on the basis of collective licensing tariffs, since the use of this cinematographic adaptation right is comparatively more intrusive. In several places, the NCB mixed the reporting on mechanical rights with that on synchronisation rights.

26

All CMOs reviewed classified categories of rights/types of use by usage specifics, i.e., by the physical or virtual settings in which copyright use occurs (E3). Such a labelling was made by most CMOs for all categories of rights/types of use except for the residual classes, while only one CMO labelled various categories of rights/types of use based on licensing specifics (e.g. special contracts/standard contracts) or billing modalities (e.g. direct distributions) instead of the usage specifics. However, the separation based on different criteria of the usage specifics led to an inconsistent presentation of business figures within many reports. This was reflected, among other things, in inconsistent terminology (E4). Only five of the CMOs surveyed maintained consistent vocabulary throughout the report, i.e., they named semantically identical categories of rights/types of use equally. Twelve CMOs occasionally used different terms for the same categories of rights/types of uses, but to an extent that, in our view, made semantic matching still possible. However, two of the CMOs labelled the categories and types in a way that made it difficult to detect synonyms. Also, a comparatively large number of categories of rights (Q1) / types of use (Q3) were counted for these CMOs. Hence, despite all efforts, it is unclear whether these are actually additional categories or if they just could not be assigned to a synonym within the report. The use of a vocabulary is only consistent, if it is applied across the entire report.

27

Besides a uniform vocabulary, coherent categorisation (E5) plays a crucial role in understanding transparency reports. This means that a clear and consistent classification scheme is used throughout the report to distinguish between categories of rights and types of use. We found this to be the case for nine of the CMOs analysed. Five other CMOs used a classification scheme that was vague in places, while four CMOs used no recognisable schemes to classify categories of rights or types of use in individual sections of the report. However, the differences in the composition and number of categories reported may also be due to organisational reasons, e.g. when a CMO serves as an intermediary for other CMOs, but does not manage the repertoire for its rightholders for certain categories of rights or due to limitations in information processing.

28

Besides the heterogeneous form of their design and structure, the transparency reports complicated an analysis by additional factors. As only 10 out of 21 CMOs provided the report for the relevant financial year in English, the mapping of the labels to their general meaning was further complicated by the lack of language skills in the national languages of the reporting CMOs. Two CMOs reporting in their national language provided only scanned versions of their reports, which posed difficulties on an automatic translation process. Also, there was rarely an explanation of the semantics behind the labels used to denote the license categories, i.e., what types of licenses are covered by the indicated license category. The semantics could often only be implicitly inferred from the context, the rare clarifications in the transparency reports, and sometimes only after supplementing information sources with publicly available tariff information and familiarisation with the CMOs' very own vocabularies. Given all these challenges, matching the terms with their generic semantics was laborious, to varying degrees depending on the reporting CMO. To provide a clear overview, we summarise our findings in two problem areas:

P1: Terminology/Language: CMOs use different labels to refer to identical concepts. This inconsistency is evident in the comparison within and between the reports. Additionally the comprehensibility of the semantics behind the labels is limited by the fact that only about a half of the sampled CMOs provided the transparency reports in English.

P2: Presentation/Structure: The use of different labels by the CMOs would be a minor problem, if references were made to the generic equivalents explaining the meaning of the reported data in English. However, this completely contradicts the way the transparency reports are presented. The semantics of the labels can only be derived implicitly, if at all. Even a simple keyword-based search of the reports for word redundancies to extract meaning through contextualisation is made impossible by some CMOs by publishing the reports in a scanned form. A key aspect of the presentation is the structure of the data, i.e. the semantic and syntactic order in which it is arranged, that is, the criteria according to which the business figures are to be classified, and the data format to be used. The CMOs chose different criteria, granularities and ordering schemes for aggregating the data.

29

Overall, extracting information from the data could only be achieved at the cost of additional efforts, the use of external documents from the CMOs and a significant amount of human interpretation. Rightholders and licensees face the same hurdles, biases and uncertainties when reading transparency reports, which basically prevents “transparency” as the central goal of these reports.

4. Consolidation through structured transparency

30

In order to ensure the transparency of CMOs’ public data, it is not only necessary to make the data available to the public but also to structure the data according to uniform criteria. The introduction of a controlled vocabulary for this kind of information might be a viable measure. According to the Publications Office of the European Union, controlled vocabularies serve to organise knowledge between different actors in a harmonised way and are a foundation for the machine-readability of metadata, improving, among other things, the discovery and cross-comparison of data on the web. The Publication Office itself hosts a range of controlled vocabularies and related artefacts. [30]

31

However, as we have shown in the previous sections, there is no consensus among CMOs on how to inform the public about what categories of rights they exercise for their managed repertoire. If it existed, it would simplify processes for rightholders and licensees on the interface to CMOs. Directive 2014/26/EU states in several places that licensees, rightholders and CMOs should use industry- or EU-developed standards and procedures when exchanging data where possible.

32

The CISAC, as the umbrella organisation for CMOs, provides a few publicly available data format specifications which are to be implemented for certain business processes in the electronic data interchange (EDI) between stakeholder parties. The Common Royalty Distribution (CRD) format is one of these specifications to be used by CMOs for the reporting of royalty distributions to other CMOs and rightholders. This specification also defines lookup tables for “distribution categories” and “exploitation source types” to be used when applying the format. [31] For these, fixed codes are defined with unique references to one concept each, e.g. 20: Radio or 01: Radio broadcaster. Although the meanings of the codes given as examples for the different named resources do not translate perfectly, they describe aspects that happen in the same licensing constellation: The distribution category 20 refers to the type of use (“Radio”), while the exploitation source type 01 describes the licensee type (“Radio Broadcaster”).

33

So, while there are data interchange formats that specify the reporting on license categories, these are designed for specific use cases. In addition, the licensing contexts are also insufficiently structured within the defined data interchange formats. Therefore, introducing a domain-wide taxonomy would be a reasonable way to describe categories of rights and types of use in a controlled manner.

34

To develop a taxonomy for license categories, we followed an inductive approach based on the analysed transparency reports. First, we established classification criteria for the objects of interest. To ensure the generic applicability of the classification criteria, organisation-specific characteristics [32] are not part of it; instead, the criteria targets the subject-matter that is most common across the CMOs: the managed categories of rights and licensed types of use.

35

License categories can be described by a combination of concepts. Each elementary concept [33] is defined within a controlled vocabulary with one unique label. For the sake of illustration, we defined a set of elementary concepts which is based on the internationally harmonised copyright types manifested in the Berne Convention (BC; 179 contracting states [34]) and the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT; 110 contracting states [35]) and the derived concepts from the sample of transparency reports we examined. To map license categories to the internationally harmonised copyright types and to the broad categories of rights of CMOs, we defined the copyright types as subsets of performing rights and mechanical rights. Each license category A, characterised by a set of elementary concepts (e.g. {“playback”, “performance”}) describes a superset/superclass (⊋) of license category B, which is described by at least one additional concept (e.g. {“playback”, “background”, “performance”}).

36

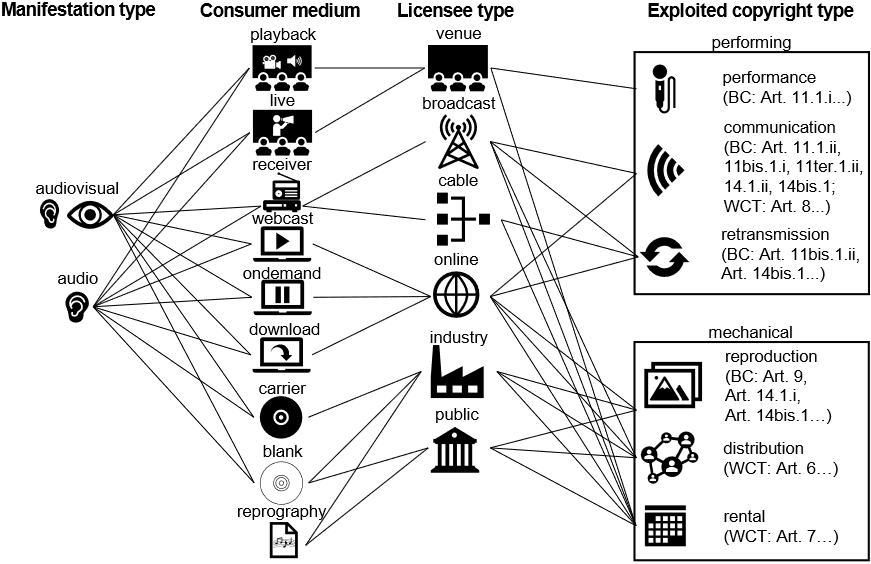

Each license category described by the same concepts contains the same features, but the order in which the labels of the concepts are textually concatenated in the form of compounds represents their hierarchy in the actual taxonomy. To achieve non-arbitrary concatenation, a fixed scheme had to be established. During our study, we identified four metaconcepts to which we assigned the elementary concepts. As shown in Figure 4, we propose that a license category is denoted by a tuple of four defined elementary concepts – following the pattern (Manifestation type, Consumer medium, Licensee type, Exploited copyright type) according to the order of their corresponding metaconcepts. (note: to see the graphics in a larger format, please download the pdf version of the article.)

Figure 4: Mapping of the elementary concepts and their interrelations within the consideration of the four metaconcepts

37

In line with the proposed definitions we mapped the license categories of those twelve CMOs that reported amounts per license category for each representation agreement (Directive 2014/26/EU, Annex 2.d.i). For each CMO-specific label for a reported license category, we disambiguated the quadruplet described above. In case a matching elementary concept for one of the four metaconcepts couldn't be identified, a placeholder (?) was inserted.

38

We made an exception for those license categories that did not qualify for a specific type of copyright or could not be classified as either performing or mechanical rights: these were assigned to the virtual concept “mixed” instead of having “?” at the last position of the quadruplet. Especially in the case of online rights, licenses are granted frequently for both performing and mechanical rights, which is why this does not always have to be the fault of the reporting, but can also correspond to the exploitation practice of a CMO. [36] Table 4 shows how many placeholders per metaconcept were introduced to describe terms for which no elementary concept corresponding to this metaconcept could be assigned. Overall 115 labels reported by the CMOs were mapped to 52 generic terms.

Table 4: Number of placeholders introduced per metaconcept for the mapping of the CMO-specific labels to the concepts

|

Manifestation type |

Consumer medium |

Licensee type |

Exploited copyright type |

|

32 |

24 |

12 |

11 |

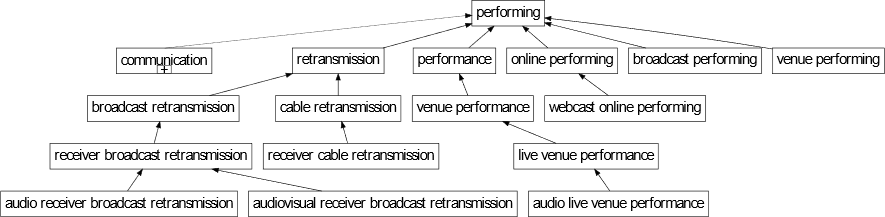

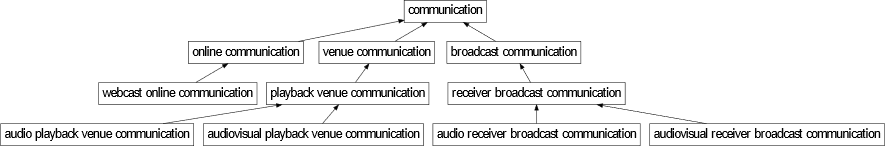

39

For the final taxonomy [37] all classes that broke the scheme, in a sense where between two specified elementary concepts at least one elementary concept was not substituted by a placeholder (n = 8), were removed. The reason for this was the implementation of the monohierarchical structure of the taxonomy: The concatenation of the elementary concepts took place in the reading direction from left to right. Placeholders were deleted in the process. To illustrate the latter, consider the following example: (? ; ? ; venue ; communication) ↦ “venue communication” is a child node (⊊) of the ancestor node (? ; ? ; ? ; communication) ↦ “communication”. However, in reality, it should also be a child of “venue performing” and therefore a sibling of “venue performance”, a relationship that gets lost when the proposed taxonomic approach is applied, since multiple inheritance is not permitted [38].

40

The relationships between license categories can be visualised as tree structures: each root node represents a broad category of rights, while each child element represents a specialisation of its parent node (e.g., see Figure 5, Figure 6)

Figure 5: Taxonomy of “performing” rights

Figure 6: Sub-branch “communication” of “performing” rights

41

By using the proposed taxonomy license categories can be classified corresponding to a controlled vocabulary. In addition, hierarchies of different license categories can be illustrated. This is not only useful for classifying the license categories but also for aggregating amounts on them, e.g., as listed in the transparency reports.

42

The formal approach based on the definition of elementary concepts and their assignment to metaconcepts in a predefined order means that the hierarchy can be generated automatically. Based on these fixed rules, the taxonomy can be extended according to a fixed pattern and thus revised without substantial changes. Therefore, as licensee types and consumer media are subject to adaptation as new exploitation channels emerge, the taxonomy presented above can be extended accordingly.

43

Yet, as mentioned earlier, taxonomies are only capable of displaying monohierarchical inheritance. Thus, CMOs have to stuck to the predefined inheritance logic and consolidate their information according to it – or a structuring concept other than a taxonomy must be used.

5. Developing an ontology of collective rights management

44

With the help of the proposed taxonomy, license categories of CMOs can be annotated in a consistent way. However, taxonomies are not sufficiently expressive as they are limited to monohierarchical structures and a limited scope of classes. Given how specific the needs of licensees and rightholders can be, the classes provided with annotations might be too generic to reflect the information required by licensees or rightholders.

45

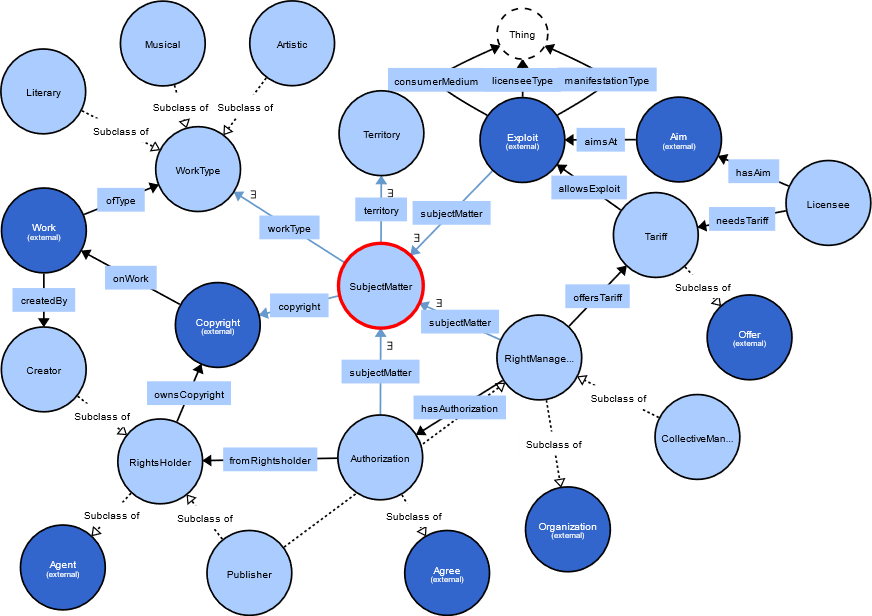

Another approach to structure the information on license categories is to formally define the permissions and constraints of each license category and to allow for the aggregation of schemes according to criteria set dynamically by stakeholders. This can be done with the help of Rights Expression Languages (REL). However, existing RELs are difficult to use in specific application contexts because they are – in high contrast to taxonomies – too expressive. [39] This is reflected in the fact that the focus of RELs is on the syntactic and not on the semantic level of expression. To enrich RELs with semantics and to bring them into the context of the application domain of Intellectual Property Rights, the IPROnto was developed, which combined several RELs (ODRL, Creative Commons, MPEG-21) and put them into the overall context of the WIPO framework. A successor to IPROnto is the Copyright Ontology, which defines three models for a common understanding of the creation, legal basis and use cycle of copyrights and related rights in works of intellectual property. [40]

46

We drafted a minimalistic ontology using the W3C standards Resource Description Framework (RDF) and Web Ontology Language (OWL), which put the concepts and their relationships defined in the Copyright Ontology into the context of CRM. [41] The ontology is visualised in Figure 7. [42]

Figure 7: A minimalistic ontology of collective rights management (visualised with WebVOWL)

47

With the help of the ontology, logical statements can be formulated. For example, an instance of the class “Aim” defines a motivation of a “Licensee” to use a “SubjectMatter” of a “Copyright” [43], which refers to a “Work” and is owned by at least one “RightHolder”. “SubjectMatter” is further specified by the types of works, the territories, as well as other specifics such as those highlighted in the previous section, for which the authorisation of a “CMO”, the licensing and thus also the utilisation of rights takes place.

48

With a well-defined model, the data publicly reported by the CMOs can be marked up, allowing them to be classified in the overall CRM framework. For example, information on revenue generated from license categories in transparency reports can be formatted in platform-independent and RDFa-enabled HTML instead of a PDF file. Using RDFa, license categories can be marked as instances of ontological concepts and their interrelations. Transparency reports produced in this way would then be machine-readable and thus suitable for comparison with automated agents. The same applies to the publication of tariff information. The proposed steps would enable interested parties to understand CMO services in an accessible way, having to get familiar with only one controlled vocabulary used to describe these kind of services. Furthermore, the enrichment of service or tariff information with structured data would offer a possibility to aggregate information across CMOs: For example, query-based services can be developed to compare tariff or service information between CMOs [44] or to identify macroeconomic dynamics through the visualisation of inter-CMO cashflows [45].

6. Conclusion and final remarks

49

In the EU, national laws are gradually being harmonised as part of the Digital Single Market strategy. Harmonisation of CMO activities is an important catalyst for an increased competition and consolidation in the CRM market. However, an important prerequisite is transparency, which serves as the basis of information required for objective decisions by stakeholders. Transparency can be prescribed by law by specifying what information must be made public and how.

50

Yet, the current state of the EU internal market shows that the information to be published by CMOs is specified too vaguely. The lack of a uniform classification system for license categories and a structured reference point for the business concepts has led to an inconsistent provision of information by CMOs. The steps that need to be taken to support the transformation of public information about CMOs into insights were discussed in this paper. In working towards this goal, this paper followed an inductive approach: while focusing on CMOs for music copyrights, we reviewed the publication of categories of rights and types of use in the transparency reports for 21 CMOs. As we found inconsistencies regarding labelling and structuring of the data, we proposed the following consolidation process: First, a taxonomical approach for annotating license categories in music copyrights was introduced. It was based on the semantic merging of the various terms used by the analysed CMOs as well as on the introducing of a common vocabulary for concepts with a corresponding classification scheme. Second, as a more complex but semantically richer solution, a draft for an ontology was presented. As we showed, both approaches have advantages and disadvantages and require consensus building on the part of the CMOs.

51

From a political point of view, the first option for building this consensus would be to promote an organic, market-based mechanism on the part of the CMOs. In this regard, it is argued that CMOs already benefit from mutual transparency as it enables them to operate the cooperative system of mutual representation agreements. [46] Shared databases such as CIS-Net promote cross-comparison between peer societies at different levels. At the operational level, they enable them to cross-check uses with each other's repertoires. At the strategic level, they can provide CMOs with a reference point for identifying their core competencies and help them determine their position in an increasingly dynamic market environment. For example, economies of scale from multi-territory licensing in the online sector could relieve the burden on smaller CMOs and allow them to specialise and improve their services in analogue licensing. Reciprocal transparency could play a crucial role in defending the relevance and competitiveness of CMOs against new and agile market players such as IMEs or modern publishing administrators. It could enhance consolidation in the CRM market and thus counteract the progressive fragmentation of copyrights. While these databases exist, they are limited to the CMOs and are not available to licensees or rightholders. Enabling public insights into this system, while abstracting from confidential data, would provide market participants with more flexibility in assessing the CRM market.

52

Here, the conflict of interest between CMOs, who benefit economically from information asymmetries, and rightholders/licensees, who are harmed by them, must be addressed. For example, according to online music service providers (OMSPs) as licensees of CMOs, the tariff setting of CMOs is non-transparent despite all applicable provisions. According to the suspicion of an OMSP, this manifests itself in the fact that the prices of competing offers converge and thus indicate anti-competitive practices, which is difficult to prove. [47]

53

Therefore, current legislative measures may not be sufficient to promote greater transparency in the disclosure of public information on license categories. Legislators might consider to enforce stricter rules for the management of public information in the CRM market. Still, to ensure consistent compliance with legislation in the CRM market, it may not be sufficient to draft binding Directives in natural language, as this leaves CMOs wide room for interpretation, thus increasing legal uncertainty and potential litigation costs. To reduce these problems, the establishment of a strict and binding data management regulation could be a sound use case for machine-readable law. [48]

54

Overall, we have shown that CMOs report differently on their managed categories of rights and types of use. Our key assumption in the discussion of this issue was that terminological harmonisation can reduce many of the problems associated with CMOs providing public information to licensees and rightholders.

55

However, the problems may lie deeper, that is, not at the level of presentation, but at the level of the actual aggregation of right bundles. CMOs license rights differently and standardised tariffs offer different bundles of rights to licensees. So before implementing a public data management module into the CRM system, it might be worthwhile to break down the bundles of rights granted to and by CMOs to their atomic level and give rightholders and licensees complete freedom in transferring and acquiring the rights for their particular needs. Still, this approach could pose even greater challenges to the CRM market, as CMOs would have to re-implement their licensing system to allow for such customised configuration options. The process costs here can only be reduced by strict and clear formulation of CMO services.

56

That said, perfect comparability may not be possible in all cases. While the categories of rights managed by CMOs are based on international law such as the Berne Convention, their licensing practices for different types of use are still subject to membership-control. The introduced classification system for license categories on the basis of metaconcepts could be helpful in this respect, but still needs to be evaluated.

*by Mihail Miller, research associate at the Institute for Applied Informatics e.V. (InfAI) at the University of Leipzig, Germany and Dr. Stephan Klingner, project manager in the research and development department at the University Computer Center at the University of Leipzig and at the Institute for Applied Computer Science e.V. (InfAI). This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research as part of the research project SO/CLEAR unstitute for Applied Computer Science e.V. (InfAI). This work der Grant 01IS18083B, which was overseen by the PT-DLR.

[1] Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market 2014, Directive 2014/26/EU (European Union) Recital 19.

[2] Sebastian Haunss, ‘The changing role of collecting societies in the internet’ (2013) 2(3) Internet Policy Review; Lucie Guibault and Stef van Gompel, ‘Collective Management in the European Union’ in Daniel J Gervais (ed), Collective management of copyright and related rights (Third edition. Wolters Kluwer 2016).

[3] Morten Hviid, Simone Schroff and John Street, ‘Regulating Collective Management Organisations by Competition: An Incomplete Answer to the Licensing Problem?’ (2017) 7(3) JIPITEC 256 <http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0009-29-45071>; Simone Schroff and John Street, ‘The politics of the Digital Single Market: culture vs. competition vs. copyright’ (2018) 21(10) Information, Communication & Society 1305.

[4] Lucius Klobučník, ‘Navigating The Fragmented Online Music Licensing Landscape In Europe A Legislative Compass In Sight?’ (2021) 11(3) JIPITEC 340 <http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0009-29-51921>.

[5] Cláudio Lucena, ‘Collective Rights Management’ in Claudio Lucena (ed), Collective rights and digital content: The legal framework for competition, transparency and multi-territorial licensing of the new European directive on collective rights management (SpringerBriefs in Law. Springer 2015).

[6] Hviid, Schroff and Street (n 4).

[7] Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market (n 2) Art. 22.

[8] ibid Annex 2.

[9] ibid Art. 22 (4)

[10] The understanding of these notions of Directive 2014/26/EU can only be derived implicitly: in Annex 2.a an exemplary list is given for types of use “e.g. broadcasting, online, public performance”; in Annex 2.b.i-ii, “categories of rights” are only mentioned in the context of the costs for rights management. In 2.b.v, the label “type of use” is used again in the context of the deductions actually taken from the licensing revenues. Based on these indications, it can be interpreted that “categories of rights” refers to rights managed in trust for rightholders and “type[s] of use” to rights of use granted to licensees by CMOs.

[11] EU-Directives generally leave room for interpretation and implementation by Member States. Although comparability is not included as a direct requirement in the transparency obligations of Directive 2014/26/EU for CMOs to be implemented by Member States, Recital 36 advocates for “comparable audited financial information specific to their activities”, which can be ensured through uniform transparency report requirements. However, the assessment of the CMO's compliance with these requirements is as debatable as their vagueness. In order to assess the compliance of CMOs with the provisions of Directive 2014/26/EU, Art. 37 and Recital 51 foresee an exchange of information between competent authorities of Member States on CMOs. This could be inter alia useful to verify the comparability of the information provided in the transparency reports.

[12] e.g. Mihály Ficsor, ‘WIPO National Seminar on Copyright, Related Rights, and Collective Management: The Establishment and Functioning of Collective Management Organizations: The Main Features’ (Khartoum, Sudan 16 February 2005) WIPO/CR/KRT/05 2 <https://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/details.jsp?meeting_id=7482> accessed 10 May 2022; Tilman Liider, ‘The Next Ten Years in E.U. Copyright: Making Markets Work’ [2007] Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal 52 <https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol18/iss1/7/> accessed 10 May 2022

[13] Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market (n 2) Recital 19, Art. 8 (4)

[14] ibid Art. 7

[15] e.g. Section 31 (5) of the German Copyright Act extends the applicability of the transfer of rights to its intended purpose

[16] This may be the case when the forms of dissemination of the works undergo technological changes.

[17] Séverine Dusollier and others, Contractual arrangements applicable to creators: Contractual arrangements applicable to creators (law and practice of selected member states : annexes III & IV, European Union 2014) 55–57.

[18] e.g. Directive 2014/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market (n 2) Art. 16 (2)

[19] e.g. Judgment of the Court of 13 July 1989. - François Lucazeau and others v Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et Editeurs de Musique (SACEM) and others. - References for a preliminary ruling: Cour d'appel de Poitiers et Tribunal de grande instance de Poitiers - France. - Competition - Copyright - Amount of royalties - Reciprocal representation contracts. - Joined cases 110/88, 241/88 and 242/88. [1989] 61988J0110, [1989] European Court reports 1989 Page 02811 (European Court) Grounds 26-33

[20] License categories refers to the subject-matter itself which is being licensed and managed by CMOs that are officially regulated by the competent authorities in the EU. It might be seen as a property of “collecting schemes” of CMOs, which have already been analysed at a more abstract level by Lucía Reguera and others, ‘Report on Collecting Schemes Europe’ (2016). However, the focus of the study was on billing practices, distribution principles (e.g., whether monitoring technologies are used) and licensing modalities of collecting societies, rather than on the administered rights in detail.

[21] CMOs for music copyrights account for the largest share of copyright collecting revenues in the EU European Commission, Directive on collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing – frequently asked questions: MEMO/14/79 (2014).

[22] European Commission, Collective rights management Directive- publication of collective management organisations and competent authorities (2021). According to Directive 2014/26/EU, this list must be updated regularly and contains information on the currently existing CMOs in the EU member states.

[23] CISAC, ‘Members Directory’ (9 August 2021) <https://members.cisac.org/CisacPortal/annuaire.do?method=membersDirectoryHome> accessed 9 August 2021.

[24] We use the term collecting societies to refer to both – collective management organisations (CMOs) and traditional organisations that do not meet the CMO-requirements of Directive 2014/26/EU but collectively represent the rights of rightholders.

[25] BIEM, ‘Members Societies’ (9 August 2021) <https://www.biem.org/index.php?option=com_licensing&view=societes&Itemid=539&lang=en> accessed 9 August 2021.

[26] At the outset of the study, it was notable that the CMOs that reported on both the categories of rights and types of use did so in a hierarchical manner. This makes sense as the broad categories of rights managed for rightholders are related to the special rights of use that the CMOs grant to licensees and which are reflected in the types of use. Based on this we derived our methodological approach and classified the “top level” rights reported in the transparency reports as categories of rights. The CMOs that reported on categories of rights and types of use in a flat way were therefore treated as having both variables counted as categories of rights (as only one hierarchical level existed). If there were additional hierarchical levels in the reports, these were classified as types of use. While this procedure is heuristic in nature, we wanted to avoid an interpretative classification per item of whether it was an affected category of right managed for rightholders or a type of use licensed to licensees of the CMO.

[27] Those CMOs for which no count is listed for Q3 and Q4 (“-”) have mixed the reporting on categories of rights and types of use, at least from our methodological point of view (see also note 26 for clarification). It can therefore be assumed that they considered these terms to be synonymous. The question mark at Q5 and Q6 indicates that CMO 1 has reported varying sets of categories of rights / types of use depending on the cooperating society.

[28] Translated from the German legal text.

[29] For example, one CMO stated in the transparency report that a breakdown per category of rights managed and type of use was not always feasible “due to IT system limitations”.

[30] Publications Office of the European Union, ‘EU Vocabularies: Controlled vocabularies’ (n.d.) <https://op.europa.eu/en/web/eu-vocabularies/controlled-vocabularies> accessed 19 August 2021

[31] Gus Jansen (APRA), ‘Common Royalty Distribution: EDI format specifications: Version 2.0, Revision 4’ (18 August 2010) CRD09-1005R4 <https://members.cisac.org/CisacPortal/consulterDocument.do?id=19514> accessed 8 September 2021

[32] Such as CMO tariff designations (e.g. “Phono Standard”) or specifics of distribution policies (e.g. “Work by Work”). These are certainly relevant metadata for comparing CMO services, but do not form the core of the legal goods in trade.

[33] Elementary means that the concept does not consist of a combination of other concepts.

[34] WIPO, ‘Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works: Status October 1, 2020’ (1 October 2020) <https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/treaties/en/documents/pdf/berne.pdf> accessed 8 September 2021.

[35] WIPO, ‘WIPO Copyright Treaty: Status on March 22, 2021’ (22 March 2021) <https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/treaties/en/documents/pdf/wct.pdf> accessed 8 September 2021.

[36] CISAC, ‘On-line repertoire definition: European rights splits (September 2020)’ (2020) <https://members.cisac.org/CisacPortal/openDocumentPackDP.do?item=item5&docPackId=174> accessed 12 August 2021.

[37] Mihail Miller, ‘Collective Rights Management Taxonomy’ (2022) <http://dx.doi.org/10.25532/OPARA-178> accessed 19 July 2022

[38] The broad categories of rights “performing” and “mechanical” where only introduced for practical reasons – to allow a mapping of collecting schemes of those CMOs that did not disaggregate information on the actual copyright types.

[39] Renato Ianella, ‘Open Digital Rights Language (ODRL)’ (2007) <https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/41230497.pdf> accessed 22 September 2021.

[40] Roberto García, ‘A Semantic Web Approach to Digital Rights Management’ (2006).

[41] The reused concepts are marked as “external” and highlighted darker in Figure 6.

[42] Stephan Klingner, ‘Collective Rights Management Ontology’ (2022) <http://dx.doi.org/10.25532/OPARA-176> accessed 19 July 2022

[43] “Copyright” is defined as a superclass of other rights like the "CommunicationRight" in García's model, which is based on the understanding of the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

[44] García Roberto and Gil Rosa, ‘Copyright Licenses Reasoning an OWL-DL Ontology’ (2009) 188 Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications 145.

[45] One example of a tool with such functionality can be accessed here: <https://creativeartefact.org/artefacts/statistics/statistics_international/>. The data for this tool refers to the business year 2019 and was compiled manually. Updating and chronologising this database would be possible, but would require introduction and application of appropriate data formats.

[46] WIPO, ‘WIPO Good Practice Toolkit for Collective Management Organizations (The Toolkit): A Bridge between Rightholders and Users’ (2021) <https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_cr_cmotoolkit_2021.pdf> accessed 25 October 2021.

[47] European Commission and Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, Study on emerging issues on collective licensing practices in the digital environment : final report (Publications Office 2021) 111–112. The annex to this report (262-380) contains a natural language listing per Member State of the types of use managed by the studied CMOs and protected by their respective national legislations. This listing can serve as input for the further development of the classification system introduced in this paper and later as a uniform basis for CMOs' reporting on the rights they manage.

[48] Patrick A McLaughlin and Walter Stover, ‘Drafting X2RL: A Semantic Regulatory Machine-Readable Format’ [2021] MIT Computational Law Report <https://law.mit.edu/pub/draftingx2rl>.

Fulltext ¶

-

Volltext als PDF

(

Size

781.2 kB

)

Volltext als PDF

(

Size

781.2 kB

)

License ¶

Any party may pass on this Work by electronic means and make it available for download under the terms and conditions of the Digital Peer Publishing License. The text of the license may be accessed and retrieved at http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/dppl/DPPL_v2_en_06-2004.html.

Recommended citation ¶

Mihail Miller, Stephan Klingner, Transparency Reports of European CMOs: Between legislative aspirations and operational reality – comparability impending factors and solution strategies, 13 (2022) JIPITEC 160 para 1.

Please provide the exact URL and date of your last visit when citing this article.