Articles

Untitled Document

urn:nbn:de:0009-29-54917

1. Introduction*

1

On 15 December 2020, the European Commission presented drafts for both a Digital Services Act (DSA) and a Digital Markets Act (DMA). [1] The DSA aims to reconcile the responsibilities of online platforms with their increased importance. Since the adoption of the e-commerce Directive two decades ago, online platforms have evolved into key intermediaries in the digital economy, as well as essential sources and shapers of information. They have developed from passive, neutral intermediaries to active co-creators of the digital sphere. In the attention economy, digital services and content are optimised to benefit online platforms’ advertising-driven business models. A central component of this business model is the moderation of content in order to encourage users to spend more time on the platform and share more personal data. Today's search engines, social media networks and e-commerce platforms determine not only which users can participate in the ecosystem or the way transactions are to be carried out via the platform but also what information corresponding users will receive.

2

Online platforms’ business models have proven vulnerable to new risks, both for society at large and for individual users. [2] Specifically, platforms have demonstrated to be a fertile breeding ground for illegal activities, such as the unlawful distribution of copyrighted works on video-sharing platforms, the sale of counterfeit goods on e-commerce platforms or the dissemination of hate speech and content glorifying violence on social media platforms. [3] The increasing spread of disinformation via such platforms is met with ever-growing concern. [4] Concurrently, the first legislative attempt at EU level to make platforms directly liable for illegal content under the Copyright Directive [5] triggered public protests [6] and criticism from academics, [7] as it was feared that this would result in online censorship.

3

Amidst the apprehension concerning disinformation on the one hand, and censorship on the other, online platforms have come under pressure to do both less and more to monitor their platforms. [8] In 2018, Facebook was accused of failing to adequately address calls for violence against Muslim minorities in Myanmar. [9] Recently, Facebook and Twitter were criticised after permanently suspending Donald Trump's account following his comments about violence at the US Capitol in 2021. [10] These examples illustrate that the debate revolving around platform responsibility reaches beyond the question of platforms’ liability in curbing illegal content. It is about the role of platforms in removing harmful content and the disadvantages of platforms having too much power in deciding what content to show.

4

In December 2020, the Commission proposed new horizontal rules for platforms in the DSA, intending to modernise the e-commerce Directive. The Commission has chosen to leave the liability regime of the e-commerce Directive untouched and instead to regulate how online platforms are to remove illegal content. The DSA provides for a tiered regulation differentiating between intermediaries, hosting providers, online platforms and very large online platforms (“VLOPs”). [11] The new obligations for these digital service providers include measures to combat illegal online content under the notice and takedown procedure, the introduction of an internal complaints management system enabling users to challenge decisions made by platforms to block or remove content, as well as far-reaching duties for VLOPs.

5

This article aims to provide an overview of the tiered obligations and to critically evaluate the regulatory approach of the DSA. The article questions the choice of maintaining the passive/active distinction from the e-commerce Directive in relation to the liability of hosting providers, especially when considering the extensive moderation that online platforms undertake as part of their business model. It argues that a more significant leap in the liability framework for online platforms would have been to work towards better, more precise and, above all, more accountable and transparent content moderation, rather than maintaining a focus on notice and takedown. It proposes sanctioning non-compliance with DSA obligations with losing the liability exemption, turning the DSA obligations into a standard of liability for platforms. The article finds that, by opting for fines and periodic penalty payments, the DSA pulls the responsibility of intermediaries out of the realm of liability and into the area of regulation.

6

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 summarises the aims and approach of the DSA proposal. Section 3 discusses the liability regime of the e-commerce Directive, as adopted in the DSA proposal. Section 4 says out the due diligence obligations imposed by the DSA, as well as the additional obligations for hosting providers, online platforms and VLOPs. Section 5 considers the sanction regime of the DSA proposal, followed by a conclusion in Section 6.

2. Aims and approach

2.1. Background: Recent sector-specific reforms

7

Since the adoption of the e-commerce Directive in 2000, sectoral rules as well as co- and self-regulatory measures have been adopted to supplement the basic horizontal regime. [12] Self- and co-regulation was promoted inter alia with the adoption of a “Memorandum of understanding on the sale of counterfeit goods on the internet” [13] in 2011, with the establishment of an Alliance to Better Protect Minors Online [14] in 2017, with a Multi-Stakeholders Forum on Terrorist Content [15] in 2015, with the adoption of an EU Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online [16] in 2016 as well as a Code of Practice on Disinformation [17] in 2018. [18]

8

In the meantime, service providers developed tools aside from notice and takedown systems to fight illegal content on their platforms. In 2017, Amazon started cooperating with brands to detect counterfeits by tagging each product with a unique barcode. [19] YouTube uses an identification database in cooperation with rightsholders to identify illegal uploads of copyrighted videos. [20] WhatsApp had to restrict message forwarding after the rapid spread of dangerous misinformation led to deaths in India in 2019. [21]

9

Two soft law instruments, the 2017 Communication on illegal content online [22], followed by a 2018 Recommendation on illegal content online [23], aimed at improving the effectiveness and transparency of the notice and takedown procedure between users and platforms, to encourage preventive measures by online platforms, and to improve cooperation between hosting service providers, trusted flaggers and authorities.

10

Sector-specific rules have been adopted for particularly harmful types of content. The Child Sexual Abuse Directive (2011) requires member states to ensure that intermediaries promptly remove websites that contain or distribute child pornography; [24] the Counter-Terrorism Directive (2017) requires member states to ensure the prompt removal of online content that constitutes a public solicitation to commit a terrorist offence; [25] and the revised Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) 2018 requires video platforms that host content for which they have no editorial responsibility, such as videos posted by users, to take measures with regards to harmful content in the areas of terrorist and racist subject matters, child pornography and hate speech to the general public. [26]

11

The DSM Copyright Directive (2019) requires that online content-sharing service providers use their best efforts to obtain licences for content posted by their users and holds them liable for copyright or related rights infringement if they do not remove the material after notification and prevent its reappearance. [27] A 2019 regulation moreover promotes fairness and transparency of online platforms towards business users and requires platforms to provide terms and conditions that are easily understandable to an average business user. [28]

12

As part of the Digital Single Market Strategy adopted in 2015, the European Commission identified the promotion of fairness and responsibility of online platforms as an area in which further action is needed to ensure a fair, open and safe digital environment. [29] After the Von der Leyen Commission announced [30] that it would propose a new law to modernise the liability rules for online platforms, the European Parliament considered that exemptions should continue to apply to digital platforms that have no actual knowledge of illegal activities or information on their platforms. [31] The European Parliament maintained that the key principles of the liability regime are still justified, but at the same time, called for more fairness, transparency and accountability in relation to the moderation of digital content, ensuring respect for fundamental rights and guaranteeing independent redress. To this end, the Parliament proposed a detailed notice and takedown procedure to combat illegal content, as well as comprehensive rules for online advertising and enabling the development and use of smart contracts. [32] The European Council stressed that harmonised rules on responsibilities and accountability for digital services should guarantee an adequate level of legal certainty for internet intermediaries. [33]

2.2. Policy objectives

13

With the DSA, the Commission aims to improve the protection of consumers and their fundamental rights in the online area as well as to create a uniform legal framework regarding the liability of online platforms for illegal content, including requirements for more algorithmic transparency and transparent online advertising. [34] Relying on Article 114 TFEU as a legal basis for the DSA, the Commission wants to prevent a fragmented legal landscape, because “(…) several Member States have legislated or intend to legislate on issues such as the removal of illegal content online, diligence, notice and action procedures and transparency”. [35] The objective of ensuring uniform protection of rights and uniform obligations for businesses and consumers throughout the internal market poses the main reason for implementing the DSA as a regulation, [36] which minimises the possibilities of Member States amending the provisions.

14

At the same time, the Commission remains limited by the objective of harmonising rules for the benefit of the internal market, as liability rules are predominantly national. [37] This partially explains why the Commission has retained the liability exception, which operates above national liability rules, rather than specifying new obligations in the form of a standard of care for online platforms. [38] The DSA only contains EU rules on the liability exemption for intermediary service providers—the conditions under which intermediary service providers incur liability continue to be determined by Member States’ rules. [39]

15

The impact assessment considered three alternatives for modernising the liability rules for hosting providers. The first option was to codify the 2018 Recommendation on illegal content, establishing a set of procedural obligations for online platforms to address illegal activities by their users. The obligations would also include safeguards to protect fundamental rights and improve cooperation mechanisms for authorities. [40] The second option was full harmonisation, promoting transparency of recommendation systems and including a “Good Samaritan” clause to encourage service providers to take voluntary measures to combat illegal activities (see further Section 3.4 below). [41] The third option would clarify the liability regime for intermediary service providers, provide for an EU governance system for supervision and enforcement, and impose stricter obligations on VLOPs. [42] The Commission opted for a combination of these options that maintains the core liability rules of the e-commerce Directive and introduces additional obligations for large platforms.

2.3. Scope

16

Overall, the DSA package results in the following set of rules: an ex-ante regulation in the DMA; ex-post liability rules from the e-commerce Directive implemented in Chapter II DSA; new obligations in Chapters III-IV DSA; and sector-specific regulations mentioned in DSA Article 1(5).

17

Chapter I of the DSA lays down general provisions regarding subject matter and scope. The DSA is set to have extraterritorial effect, meaning the regulation will apply whenever a recipient of intermediary services is located in the EU, regardless of the place of establishment or residence of the service provider. [43] Additionally, a “substantial connection” of the service provider with the EU is required, which is to be considered when the intermediary service has a significant number of users within the EU or where the provider targets its activities towards one or more Member States. [44]

18

In terms of its material scope, the DSA contains new obligations for digital service providers with respect to illegal content. The definition of illegal content is comprehensive, including “information relating to illegal content, products, services and activities”. [45] It could therefore be information that in itself is illegal, such as illegal hate speech or terrorist content and unlawful discriminatory content, or information that relates to illegal activities, such as the sharing of images showing the sexual abuse of children, the unlawful sharing of private images without consent, cyber-stalking, the sale of non-compliant or counterfeit products, the unauthorised use of copyrighted material or activities that violate consumer protection law. [46] Otherwise, illegal content continues to be defined according to the member states’ national laws. [47] The DSA does not distinguish between different types of infringement with respect to any of the obligations. This means that criminal offences, intellectual property rights violations and infringements of personal rights all face uniform compliance rules. [48]

19

Harmful but not necessarily illegal content, such as disinformation, is not defined in the DSA and is not subject to mandatory removal, as this is a sensitive area with serious implications for the protection of freedom of expression. [49] To tackle disinformation and harmful content, the Commission wants to focus on how this content is disseminated and shown to people rather than pushing for its removal. [50]

20

The proposed DSA imposes transparency and due diligence obligations on providers of “intermediary services” [51]—the latter includes the services of “mere conduit” [52], “caching” [53], and “hosting” [54]. [55] The material scope of the DSA coincides with that of the “information society services” in the InfoSoc Directive, [56] which encompasses services normally provided (i) for remuneration, (ii) at a distance, (iii) electronically and (iv) at the individual request of a user. [57] This material scope and definition also applies to the e-commerce Directive. [58]

21

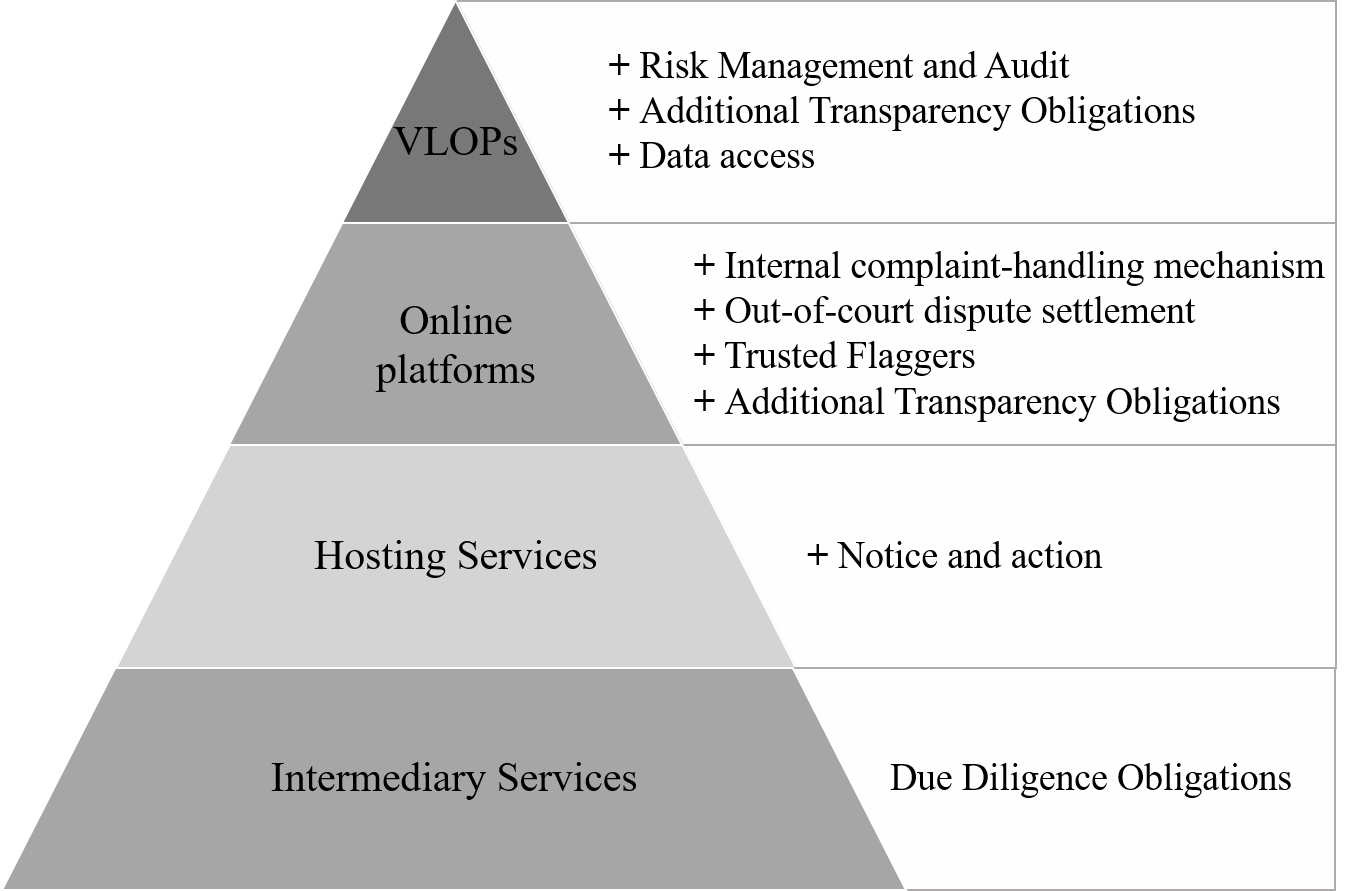

The DSA, however, extends the scope of the e-commerce Directive in several ways. One of the more notable alterations lies with the differentiation within the category of intermediary services. In addition to the provisions applying to all providers of intermediary services, the DSA proposes increased obligations for hosting providers and online platforms. [59] The DSA implements a pyramidal structure (see Figure 1 below), with general “due diligence obligations” applying to a broad group of providers of intermediary services and additional obligations only affecting certain providers of an increasingly limited category of intermediary services. The proposed obligations apply cumulatively, meaning online platforms will also need to comply with due diligence obligations that apply to intermediary services in general as well as with obligations hosting providers are subject to. Therefore, a VLOP will not only have to comply with the obligations that relate specifically to its category but also with those for “ordinary” online platforms. [60] The classification of the different intermediary services under the DSA could, however, still lead to uncertainties. For example, cloud infrastructures seem to fall under the category of online platforms (or possibly VLOPs), although they are technically not able to monitor or moderate the content they store on behalf of customers. [61]

22

Specifically, the draft proposes a classification that distinguishes in: (a) very large online platforms (VLOPs) [62]; (b) online platforms [63]; (c) hosting providers [64]; and (d) intermediary services. [65] Qualification is made based on relevant activities, not on the basis of the relevant service provider as a whole. This means that a service provider may qualify as an online platform with respect to certain activities and as a “mere conduit” for others. [66]

Figure 1: Cumulative obligations for intermediary services (simplified).

23

The principal innovative feature of the DSA is that it foresees separate, additional obligations for the subcategory of online platforms. The main difference between hosting services and online platforms lies in the dissemination of stored information to the public. While hosting services only store information, online platforms also make information available to the public. [67] General due diligence obligations for all intermediary services include establishing a single point of contact [68], incorporating certain information in the provider’s terms and conditions [69] as well as complying with transparency reporting duties [70] (see Section D.I. below). In addition to these obligations, hosting services are required to implement an easily accessible, user-friendly notice and action procedure to allow third parties to notify the provider of illegal content on the service (see Section D.II below ). [71]

24

With respect to the subcategory of online platforms, the draft aims at tightening complaint management and reporting obligations to supervisory authorities. Also, the establishment of out-of-court dispute resolution mechanisms, including the introduction of trusted flaggers and precautions against the abuse of complaints, is proposed (see Section D.III) . [72] However, there is a carve-out exception for micro and small enterprises who will not be required to comply with these additional obligations. [73]

25

For the limited subcategory of VLOPs, the proposal further foresees obligations with regard to risk management, data access, compliance, and transparency, as well as the implementation of an independent audit (see Section D.IV below). [74]

26

In a broader perspective, the proposal raises the question on the DSA’s relationship with other frameworks that contain lex specialis rules. [75] In context with the e-commerce Directive, rather than repealing the Directive, the DSA only amends certain provisions. [76] Generally, the DSA is intended to complement the e-commerce Directive and other more recent sector- or subject-specific instruments already put in place. [77] It, therefore, aims to coexist with current legislation rather than replace it.

3. Liability regime

3.1. Liability exemption

27

Chapter II of the DSA largely adopts the liability rules of the e-commerce Directive, making it clear that the Commission wished to leave the principles underlying the liability regime for hosting providers unchanged. This means that online platforms continue to be fundamentally not responsible for third-party content.

28

The e-commerce Directive created a harmonised exception to the national liability regime applicable to online platforms for unlawful material uploaded by users. According to Article 14 e-commerce Directive, service providers are exempted from liability for third-party illegal content, provided they are unaware of or fail to remove the illegal content after becoming aware of it. In practice, this has resulted in notice and takedown procedures enabling users to notify service providers of illegal content. As will be discussed further below, the DSA lays down new requirements for the notice and takedown procedure for hosting providers, extending it to a notice and action procedure (section D.I.).

29

Article 5 DSA adopts Article 14 e-commerce Directive. For mere conduits and caching services, Articles 3 and 4 DSA respectively exclude liability, while Article 5 exempts hosting services from liability as long as they remove illegal content expeditiously upon obtaining knowledge of it. The DSA only contains EU rules on the liability exemption for intermediary service providers—the conditions under which intermediary service providers incur liability continue to be determined by Member States’ rules.

30

What is new is that the DSA, in Articles 8 and 9, introduces rules regarding the orders that national judicial or administrative authorities can address to intermediaries. These orders can oblige intermediaries to cooperate with member states’ judicial or administrative authorities when acting against concrete instances of illegal content. Orders need to include a statement of reasons and information on possibilities of appeal. Articles 8 and 9 do not grant new powers but instead establish a harmonised framework for existing powers to be exercised in an efficient and effective manner. [78]

31

A reason provided in the DSA for maintaining the liability regime of the e-commerce Directive is that the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”) provided clarification and guidance for the existing rules. [79] The proposal notes that the legal certainty created has helped many new types of services emerge and expand throughout the internal market. [80] According to the impact assessment, departing from the liability exemption by imposing more legal risks on intermediaries could have a severe impact on citizens’ freedom of expression on the internet. It is argued that changing the liability regime would be prohibitively expensive for new businesses while lowering the standard for hosting providers to qualify for liability exemptions would affect security and trust in the online environment. [81] Further, alternative liability regimes were simply considered inappropriate. Creating a positive basis at EU level for determining in which cases a service provider should be held liable was rejected as this would not comply with the principle of subsidiarity. [82] The possibility of including online marketplaces in the liability regime and requiring them to obtain accurate and up-to-date information on the identity of third-party service providers offering products or activities through the platforms was considered a separate issue from the review of the horizontal liability regime set out in the e-commerce Directive. [83] The impact assessment also rejected the option of making the liability exemption conditional on compliance with due diligence obligations. Instead, it advocated for requiring compliance with these obligations separately from the liability exemption. According to the impact assessment, this would impose a disproportionate burden on public authorities and create further legal uncertainty for service providers. [84] With a view to individuals’ rights, the possibility of linking due diligence obligations to the liability exemption may have been discarded too quickly (see Section 5.2 below).

32

In addition to the liability exemption, two further pillars make up the e-commerce Directive liability regime. [85] First, the country-of-origin principle states that an online platform is only subject to the liability regime of the EU Member State in which it is established. [86] The DSA holds on to this principle, although it reduces its practical meaning by harmonising a number of significant issues at Union level. [87] Second, the e-commerce Directive prohibits EU Member States from imposing a general obligation on hosting platforms to monitor material. [88] The ECJ has drawn a blurred line between general monitoring measures, which are prohibited, [89] and permitted specific monitoring measures, in particular in the case of suspected infringement of intellectual property rights. [90] Article 7 DSA takes over the prohibition on member states stated in Article 15 e-commerce Directive imposing a general duty of supervision on intermediary services. [91] With regard to the difficulty mentioned above in distinguishing between general and specific monitoring obligations, the draft DSA now clarifies that authorities and courts may issue orders to stop infringements by specific illegal content. [92]

33

The impact assessment prepared for the DSA identified three main shortcomings of the existing liability regime: [93] i) the e-commerce Directive could discourage voluntary actions taken to fight illegal content online; ii) the concept of playing an “active” role is uncertain, [94] and iii) the e-commerce Directive does not clarify when a platform is deemed to have acquired “actual knowledge” of an infringement which triggers the obligation to remove the content. [95]

3.2. “Active”

34

The ECJ distinguishes between, on the one hand, services that assume a purely technical, automatic and passive role, which can benefit from the exemption from liability, and on the other hand, services that assume a more active role, such as optimising the ranking of offers for an e-commerce platform, which cannot benefit from the exemption. [96]

35

The Impact Assessment notes that, “(…) there is still an important uncertainty as to when it is considered that an intermediary, and in particular, a hosting service provider, has played an active role of such a kind as to lead to knowledge or control over the data that it hosts.” [97] The Impact Assessment states: “Many automatic activities, such as tagging, indexing, providing search functionalities, or selecting content are today’s necessary features to provide user-friendly services with the desired look-and-feel, and are absolutely necessary to navigate among an endless amount of content, and should not be considered as ‘smoking gun’ for such an ‘active role’.” [98]

36

In order to benefit from the liability exemptions, the distinction between a passive, neutral role and an active role remains relevant for service providers. [99] Thus, as before, the liability exemptions require that the role of the intermediary of a service is purely technical, automatic and passive, having neither knowledge of nor control over the information stored. [100] The DSA does not significantly develop this concept [101] but clarifies some aspects. First, the DSA includes a “Good Samaritan” clause [102] (see Section C.IV below). Secondly, the DSA excludes intermediary service providers from the liability exemptions if they knowingly cooperate with a user to engage in illegal activities. In that case, the platform does not provide the service in a neutral manner. [103] Thirdly, an online marketplace operator is excluded from the liability exemption if third party offers misleadingly look like the platform operator’s own offers. [104] In such a case, however, it is less relevant who controlled the offer or stored information, but much more whether service providers created the impression that the offer or information originated from them. This criterion is objectified, with the impression of an average, reasonably well-informed consumer being decisive. [105] This e-commerce liability aims to distinguish the responsibility of different types of e-commerce platforms: those who have a limited role in the transactions between users and those who play a central role in promoting the product, the conclusion of the contract and its execution. [106]

37

Given the extensive moderation that online platforms undertake as part of their business model, maintaining the passive/active distinction as a criterion for the liability of service providers seems questionable. Filtering, sorting and optimising content for profit is still seen as an activity of a purely technical, passive nature and does not lead to knowledge of illegal content on the platform. Whether this reflects the AI-moderated world of today's online platforms may rightfully be doubted.

38

In their early days, service providers were often seen as mere intermediaries bringing together different user or customer groups by reducing transaction costs. [107] Today, online platforms active on two-sided markets attract users by offering them free services or content, generating revenues by charging users on the other side of the market and through advertising. To maximise their revenues, ad-supported platforms design services to hold users’ attention to show them more advertising and encourage users to disclose more personal data in order to serve up more lucrative personalised ads. [108] In this attention economy, the design of digital services is usually optimised in favour of these advertising-driven business models.

39

While some service providers may still take up a passive, neutral role, online platforms have evolved into active co-creators of the digital sphere. [109] A central component of the advertising-driven business model lies in content moderation to encourage users to spend more time on the platform and share more personal data. Today's search engines, social media networks and e-commerce platforms determine not only which users can participate in the ecosystem or the way transactions are to be carried out via the platform but also what information corresponding users will receive.

40

With this in mind, it is difficult to maintain that online platforms offer a service of a purely neutral, technical nature. It is also difficult to discern what type of moderating is allowed and at what point it turns into an “active” role for the purpose of liability. An alternative solution would be to let go of the passive/active distinction and instead link the liability exemption to complying with the due diligence obligations in the DSA. This would effectively set a Union-wide standard of care for hosting providers and online platforms (see further Section E.II. below).

3.3. “Knowledge”

41

The e-commerce Directive does not state at which point a platform is deemed to have acquired “actual knowledge” of an infringement that triggers the obligation to remove the content. It is unclear what information is required for a notification to trigger such knowledge. [110]

42

The draft DSA clarifies that providers can obtain this knowledge through sufficiently precise and sufficiently substantiated notifications. It remains to be seen to what extent platforms will be able to hide behind an imprecise or incomplete notification in order to circumvent takedown obligations. [111]

3.4. Good Samaritan clause

43

According to the impact assessment, the ECJ's interpretation of the e-commerce Directive left a paradox of incentives for service providers: proactive measures taken to detect illegal activities (through automatic means) could be used as an argument that the service provider is an “active” service controlling the content uploaded by its users and therefore cannot be considered as falling within the scope of the conditional exemption from liability. [112] As a result, the e-commerce Directive could discourage voluntary “Good Samaritan” measures to remove or detect unlawful content. [113] The 2018 Recommendation on Illegal Content Online already included a “Good Samaritan” clause but was merely a non-binding instrument. [114]

44

The proposal to include a “Good Samaritan” clause in hard law had been proposed by several academics and will be met with approval. [115] It is consistent with the policy goal of getting service providers to better monitor their platforms without violating the prohibition on general monitoring obligations in the DSA. [116]

45

Article 6 DSA includes a “Good Samaritan” clause, which clarifies that liability privileges do not cease merely because online intermediaries voluntarily take measures to remove or detect unlawful content, as long as these activities are undertaken in good faith and in a diligent manner. [117] The provision seeks to create incentives for service providers to take more initiative against illegal content without any immediate risk of being labelled “active” and losing immunity. The rule does not apply to activities of service providers involving user information that is not illegal, so service providers need to be sure that the content in question is illegal. The clause also applies when service providers take such measures to comply with requirements of other Union law instruments, for instance, under Article 17 of the DSM Copyright Directive or the Regulation on Combating Terrorist Content Online. [118]

46

The wording of Article 6, however, leaves much to be desired. The provision only states that voluntary measures taken by intermediaries on their own initiative should not be the sole reason for losing the liability exemption. [119] Article 6 does not protect intermediaries against the fact that voluntary actions could lead intermediaries to have “actual knowledge” of illegal content in the meaning of Article 5(1) DSA, which would require them to remove the content in order to avoid liability. [120] Kuczerawy names the example of a moderator trained to review for one type of illegality, who fails to recognise that a particular video is illegal on another ground. Not removing that content that was reviewed “could still result in liability because the host ‘knew’ or ‘should have known’ about the illegality”. [121]

47

Neither does the provision guarantee that the intermediary is considered passive and neutral. Thus, it remains open to interpretation if, for instance, unsuccessful voluntary actions might not be considered “diligent”, resulting in intermediaries losing their exemption from liability. [122] The provision, moreover, leaves open the possibility of liability exemptions being revoked due to service providers having an active role in other aspects, such as in presenting the information or the offer. [123]

48

Overall, the provision protects an intermediary only from being considered “active” solely on the basis of actions taken to remove illegal content voluntarily. The “Good Samaritan” clause illustrates the difficulties of trying to hold on to the legal distinction between passive and active service providers in the moderated online world.

4. Obligations

4.1. Due diligence obligations

49

Chapter III of the DSA lays down due diligence obligations. Section 1 covers obligations applicable to all intermediary service providers.

50

Looking only at the exemption from liability, the DSA does not significantly change the status quo. [124] The DSA does not raise the standard for hosting provider liability in civil proceedings before national courts. However, the proposal provides for a number of information and due diligence obligations for platforms in Chapters III and IV, which impose new administrative duties on online platforms.

51

According to Article 10, hosting providers will have to set up a one-stop shop for authorities. [125] The focal point will be required to cooperate and communicate with supervisory authorities, the EU Commission and the European Committee on Digital Services (created under the DSA) in relation to their obligations under the DSA. Online intermediaries based outside the EU (e.g., in the UK) but operating in the EU will have to appoint an EU legal representative for this purpose. [126]

52

In addition, Article 12 provides for an obligation for service providers to include in their general terms and conditions information on “any policies, procedures, measures and tools used for the purpose of content moderation, including algorithmic decision-making and human review”. [127] Finally, according to Article 13, providers are obliged to publish annual reports on the content moderation they carry out. [128] Separate transparency obligations apply to platforms under Article 23 (see 5). Furthermore, Articles 8 and 9 introduce procedural measures and oblige providers to inform the competent authorities of the measures they have taken to combat infringements (Article 8) and harmonise which elements this information must contain (Article 9).

4.2. Hosting providers: Notice and action mechanism

53

Chapter III, Section 2 of the DSA introduces additional obligations for hosting services, primarily with regard to their notice and takedown systems.

54

With reference to illegal content, the draft DSA clarifies the obligations of platforms to benefit from the liability exemption. The proposal no longer refers to a notice and takedown procedure but to a notice and action mechanism. However, it does not envisage any dramatic changes but rather harmonises some procedural aspects for these mechanisms [129] that were already laid down in the laws of many member states. [130]

55

According to Article 14 DSA, hosting service providers must implement a user-friendly and easily accessible notice and action procedure that allows users to report illegal content. [131] It requires a timely, thorough and objective handling of notices based on uniform, transparent and clear rules that provide for robust safeguards to protect the rights and legitimate interests of all data subjects, in particular their fundamental rights. [132]

56

While the proposal provides for specific rules in the case of repeated infringements, it does not go so far as to impose a “notice and stay down” obligation, which would require hosting providers to ensure that illegal content does not reappear. [133] The ECJ has already explicitly pointed out that a platform must effectively contribute to preventing repeated infringements. [134] The new obligations to temporarily block accounts of repeat offenders are, therefore, a rather conservative codification of this case law. It remains to be seen how platforms will deal with tactics by repeat offenders to avoid measures, such as switching back and forth between different accounts. [135]

57

Article 14 specifies what information hosting service providers must request in order to be aware of the illegality of the content in question. [136] Article 14 requires that notifications must contain, in addition to the reason for the request, a clear indication of the location of the information, in particular the precise URL address, as well as the name and details of the requesting party and a statement of good faith. The requirement of precise information codifies ECJ case law which states that injunctions targeting specific content are admissible, while general injunctions are not. [137] Article 14 also clarifies that notices containing the elements mentioned above are presumed to be actual knowledge of illegal content, in which case the provider loses the exemption from liability under Article 5. [138] In this way, the DSA aims to remove the uncertainty regarding “knowledge” discussed above. [139]

58

Hosting service providers must notify users of the decision in a timely manner, inform them of possible remedies as well as of the use of any automated systems. [140] If the hosting service provider decides to remove or block access to the reported content, it must notify the user in accordance with Article 15 no later than the time of removal or blocking of access with a clear and specific justification. This is independent of the means used to trace, identify, remove or block access to this information. [141] The justification must contain certain information and be easily understandable given the circumstances. [142]

4.3. Online Platforms: Procedural and transparency obligations

59

Chapter III, Section 3 of the DSA contains further provisions for online platforms, excluding micro or small enterprises. [143] An “online platform” is a “hosting service which, at the request of a recipient of the service, stores and disseminates to the public information, unless that activity is a minor and purely ancillary feature of another service and, for objective and technical reasons cannot be used without that other service, and the integration of the feature into the other service is not a means to circumvent the applicability of this Regulation”. [144] As previously mentioned, the distinguishing element of an online platform is, therefore, the dissemination of users’ information to the public.

60

Article 17 obliges online platforms to set up an easily accessible and free electronic complaints management system. The complaints system must enable users to appeal against decisions made by the platform that user information is illegal or violates the general terms and conditions. This applies to decisions to remove content, to suspend services to users or to terminate a user's account altogether. [145] It is noted that platforms must not make such decisions solely by automated means. [146] This effectively creates a human oversight obligation that can prove costly for platforms. For decisions arising from the preceding mechanism, users must have the possibility to resort to out-of-court dispute resolution mechanisms (Article 18). This mechanism neither replaces other legal or contractual means of dispute resolution (courts or arbitration) [147] nor does the DSA create its own substantive user rights. [148]

61

Article 19 codifies the role of “trusted flaggers”: specific entities (not individuals) that are given priority in handling complaints, thus streamlining the procedure and increasing accuracy. Member States can grant trusted flagger status to entities such as NGOs or rightholders’ organisations, provided they have the necessary expertise, represent collective interests and are independent of any online platform and submit their reports in a timely, diligent and objective manner. [149] Priority in the processing of their notifications, however, seems to be the only advantage associated with the trusted flagger status. [150]

62

Article 20 regulates the conditions under which services are temporarily blocked for users who frequently provide “manifestly illegal content”. [151] Users who frequently submit obviously unfounded reports or complaints should also be blocked after prior warning. [152] The criteria for abuse must be clearly stated in the general terms and conditions [153] and must take into account the absolute and relative number of obviously illegal content or obviously unfounded reports or complaints, as well as the severity of the abuses and their consequences, and the intentions pursued. [154] According to Article 21, the law enforcement authorities must be notified immediately if “(…) a serious criminal offence involving a threat to the life or safety of persons (…)” is suspected. [155]

63

In addition to the general transparency obligations listed above, Article 23 requires online platforms to publish information on out-of-court disputes, on blocking under Article 20 and on the use of automated means for the purpose of content moderation. [156] It remains to be seen how this relates to Article 17's prohibition on relying exclusively on automated content moderation.

64

Article 22 DSA also provides for a “know your customer” obligation, according to which online marketplaces, where traders offer products or services, must collect detailed information on the identity of traders. [157] Platforms must make reasonable efforts to ensure that the information provided is accurate and complete. The duty to identify traders means a new, potentially costly layer of administration for platforms. [158] However, it should be noted that micro or small businesses are exempt from these obligations. The “know your customer” obligation should help detect rogue traders and protect online shoppers from counterfeit or dangerous products.

65

Finally, advertising-financed online platforms must provide transparency to users about personalised advertising. Article 24 obliges online platforms to provide their users with real-time information about the fact that the information displayed is advertising, why they are seeing a particular advertisement and who has paid for it. The platforms must also ensure that sponsored content is clearly marked as such. [159] However, a ban on personalised advertising, as proposed in a parliamentary report, is not suggested. [160]

4.4. VLOPs: Additional risk management and transparency obligations

66

Finally, Chapter III, Section 4 DSA introduces the strictest compliance, accountability and risk management requirements to systemically important platforms. According to Article 25, these are platforms that provide their services to active users in the Union whose average monthly number is at least 45 million people or 10% of the Union population. [161] Systemically important platforms are thus defined quantitatively and not, as under the DMA, via their gatekeeping function and their impact on the internal market. The calculation method explicitly takes into account the number of active users. The platform is not subject to the special regime until the digital services coordinator has decided to that effect. [162]

67

For these VLOPs, the Commission considers further obligations necessary due to their reach in terms of the number of users and “(…) in facilitating public debate, economic transactions and the dissemination of information, opinions and ideas and in influencing how recipients obtain and communicate information online (…)”. [163] The systemic relevance is that the way VLOPs are used “(…) strongly influences safety online, the shaping of public opinion and discourse, as well as on online trade”. [164]

68

In addition to the obligations imposed on gatekeepers under the DMA proposal, the DSA primarily addresses risk mitigation in content moderation situations for the largest platforms. Under Article 26, VLOPs will be required to conduct an annual risk analysis addressing “(…) any significant systemic risks stemming from the functioning and use made of their services in the Union”. [165] The risks to be assessed relate to the dissemination of illegal content through their services; to the adverse effects on the exercise of fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression and information and the prohibition of discrimination; as well as to the intentional manipulation of the service with adverse effects on the protection of public health, minors, social debate, electoral processes and public safety. This includes manipulation through inauthentic use or automated exploitation of the service. These risk assessments should particularly focus on the impact of the platform’s moderation and recommendation systems. [166]

69

These risks should be mitigated by appropriate, proportionate and effective risk mitigation measures (Article 27). As examples of such measures, the DSA mentions adapting content moderation and recommendation systems, limiting advertising, strengthening internal supervision, adapting cooperation with trusted flaggers and initiating cooperation with other platforms through codes of conduct and crisis protocols. [167] Section 5 of Chapter III introduces codes of conduct (Articles 35-36) and crisis protocols (Article 37) as forms of self-regulation promoted by the Commission.

70

Per Article 28, VLOPs are also subject to an independent audit at their own expense at least once a year, which assesses compliance with the due diligence obligations in Chapter II and as well as the commitments in accordance with codes of conduct. [168]

71

Further transparency obligations are imposed in relation to the use of recommendation systems (Article 29) and online advertising (Article 30). For recommendation systems, VLOPs must set out the main parameters used in their recommendation systems in an understandable way and elaborate any options they provide for users to influence the main parameters. Also, users must have at least one option to use the service without profiling. [169] The added transparency of online advertising forces ad-driven platforms to compile and provide information about the ads and the advertiser. It is to be expected that an obligation to disclose such sensitive information will be subject to intense discussions in the legislative process. [170]

72

Finally, VLOPs must ensure the digital services coordinator access to data (Article 31) and appoint a compliance officer (Article 32) who is responsible for monitoring compliance with the regulation and preparing reports (Article 33).

73

The asymmetric structure of obligations in the DSA offers advantages in that it reflects the central role that the largest platforms play in curbing illegal and problematic content. As such, the DSA represents a significant change in the regulatory oversight exercised over large hosting providers. Nevertheless, to prevent harmful activities from being shifted from VLOPs to smaller players, it could be considered to impose obligations to assess and mitigate systemic risks on all or more online platforms on a pro-rata basis and not only to VLOPs.

5. Enforcement and penalties

5.1. Competences

74

Chapter IV of the DSA introduces a number of detailed and far-reaching enforcement measures and mechanisms. Unlike the e-commerce Directive, the DSA specifically regulates the national authorities responsible for applying the regulation. [171] In this respect, the DSA follows the example of the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”). [172] The supervisory authority is determined by the location of the service's main establishment (Article 40).

75

In order to speed up enforcement by national authorities, [173] each Member State must appoint a digital services coordinator: an independent and transparent authority (Article 39) responsible for supervising intermediary services established in the respective Member State and for coordination with specialised authorities (Article 38). The basic idea seems to be to designate a primary contact in cases in which Member States have several competent authorities. Article 41 gives considerable powers to the digital service coordinators. They can request cooperation from anyone with relevant information about infringements, conduct on-site inspections of premises used by intermediaries, including the right to seize information related to a suspected infringement, as well as the power to question any employee. Although the measures are mainly aimed at intermediaries, the coordinators may also impose fines or periodic penalty payments on other entities or persons who fail to comply with the rules. Similar to the GDPR, the DSA provides for a European coordinator—the “European Board for Digital Services”—in Articles 47-49.

76

VLOPs are subject to a separate and detailed enforcement regime. If a digital services coordinator finds that such a platform is in breach of any of the obligations for VLOPs, it will be subject to enhanced supervision under Article 50 and required to draw up an action plan (and possibly a code of conduct). If the action plan is not satisfactory, further independent audits may be ordered, and Commission intervention is possible.

77

The Commission is to be given very wide powers in relation to VLOPs. Similar to the Commission's role in the field of EU competition law, [174] Article 51 ff. allows for investigations, interim measures, undertakings and a special sanctions regime that includes fines (Article 59) and periodic penalty payments (Article 60). In the event of persistent non-compliance, the Commission may request the national coordinators to act according to Article 41(3) and request the national judicial authorities to temporarily suspend services or access.

78

With respect to VLOPs, the DSA thus envisages a highly centralised regulatory model with the Commission as the sole regulator. This choice appears to be a response to the difficulties that arose in enforcing the GDPR; experience with the GDPR has shown that the Irish data protection authority was overwhelmed and, therefore, slow to respond to complaints. Integrating the national digital services coordinator into the European Board for Digital Services allows the Commission to circumvent the country-of-origin principle and avoid that all complaints about big tech platforms end up with one national authority. The solution in the DSA maintains the country-of-origin principle while ensuring that it can enforce the DSA swiftly. [175] At the same time, the Commission is no impartial, independent regulator, which is the norm in media and data protection law. [176] Creating an impartial, independent DSA-regulator at the Union level could help ensure a unified approach to content moderation requirements for VLOPs, even if creating a new regulator may be difficult to achieve. [177]

79

Appointing the Commission or a newly to be created entity as DSA-regulator also means that service providers will be supervised by two regulators: a data protection authority for data protection issues and a digital services coordinator for DSA issues. It has been proposed that an interaction between these authorities will be essential as service providers will need to process a large amount of personal data when fulfilling the complaint management obligations. [178]

5.2. Sanctions: Losing the liability exemption?

80

Failure to comply with the rules of the DSA may, in the most serious cases, result in fines of up to 6% of the annual turnover of the service provider concerned. Providing false, incomplete or misleading information or failing to submit to an on-site inspection may result in a fine of up to 1% of annual turnover (Article 42).

81

Under the DSA approach, it may appear that the obligations essentially set a standard of liability for platforms, but given their sanction regime, this is ultimately not the case. The sanctions for non-compliance with DSA obligations are fines as well as periodic penalty payments. It is not the loss of exemption from liability. Linking the exemption from liability to compliance with the obligations could have been an alternative, possibly more deterrent, solution to fines. While the fines for VLOPs are potentially huge, they may end up being significantly lower than the maximum, as experience from competition law shows. [179] Wagner and Janssen note that antitrust fines have not pushed platforms into compliance, similarly to GDPR fines. [180] At the same time, the detailed obligations foreseen in the DSA could be more burdensome for service providers than a liability approach where platforms can choose how best to achieve remediation. [181]

82

The goal of preventing over-blocking by platforms appears to be the first reason why a regulatory approach was preferred, as it is meant to ensure some control over how platforms decide on removing illegal content. Yet, this outcome may also have been achievable by requiring compliance with due diligence obligations in order to enjoy the liability exemption. This would have effectively set a Union-wide standard of care for hosting providers and online platforms that reflects their role in moderating content. This option would simultaneously have allowed moving away from the passive/active distinction, which no longer fits today’s online platforms.

83

A second reason why the liability route was not chosen can be found in the limits of harmonisation due to the principle of subsidiarity. The legal basis for the internal market allows the Commission to adopt rules that affect the liability rules of the Member States, but only to the extent necessary for the internal market. Establishing a positive liability standard at the EU level may, therefore, have been difficult to achieve on the basis of Article 114 TFEU. However, not only do the current rules already considerably affect liability under national rules, but the EU has also adopted liability rules in other contexts, such as antitrust damages actions. [182]

84

The choice to sanction violations of the DSA by a fine rather than by loss of exemption from liability impacts not only service providers but also individuals’ rights and remedies. Private individual remedies such as claims for damages or injunctive relief do not follow the duties set out in the DSA. Injured parties continue to rely on national tort law provisions when seeking redress, which is not helped by the liability exemption. Vis-à-vis VLOPs, their extensive moderation policies bear the question of whether this approach is still valid today and in the foreseeable future. [183]

85

Finally, linking the obligations in the DSA to the liability exemption may have encouraged the use, development and improvement of automated detection tools of hosting platforms. Machine learning technologies already enable platforms to rely on automated tools both to perfect their business models and (often relatedly) to detect illegal activity online. While problems with over-blocking in relation to censorship must certainly be avoided, automated detection tools may well improve into (the most) effective means of detecting and removing illegal content online. [184] In this regard, a more significant leap in the liability framework for online platforms would have been to work towards a better, more precise, and above all, more accountable and transparent content moderation, rather than maintaining a focus on notice and takedown.

6. Conclusion

86

The DSA is an ambitious proposal seeking to reconcile the responsibility of service providers, hosting providers and online platforms with their changed role in optimising and moderating content on their platforms. This goal, however, is not reflected in the liability regime of the DSA in itself, which adopts the liability rules of the e-commerce Directive essentially unchanged. Maintaining the passive/active distinction as a criterion for liability of service providers seems questionable given the extensive moderation that takes place on their platforms. Filtering, sorting and optimising content for profit is still seen as an activity of a purely technical, passive nature and does not result in “actual knowledge” of illegal content on the platform. Whether this reflects the AI-moderated world of today's online platforms may rightfully be doubted.

87

Nevertheless, the DSA brings significant changes to the regulatory framework for service providers. The new obligations and procedural requirements, particularly in relation to the notice and action regime, create a new regulatory approach, part of which is specifically targeted at those providers most likely to engage in problematic practices. While the core exemption from liability remains, service providers will be required to have mechanisms in place to monitor violations.

88

In conjunction with the draft DMA, the asymmetric rules reflect the central role that the largest platforms play in the digital economy today. The additional transparency and due diligence obligations on online platforms and VLOPs recognise the critical role they can play in curbing illegal and problematic content. As such, the DSA represents a significant change in the regulatory oversight exercised over large hosting providers.

89

Overall, the DSA moves the responsibility of intermediaries away from the area of liability and deeper into the realm of regulation. Under the DSA approach, it may appear that the obligations essentially set a standard of liability for platforms. But given the sanction regime, this is ultimately not the case. The sanctions for non-compliance with DSA obligations are fines and periodic penalty payments, not the loss of exemption from liability.

90

The goal of preventing over-blocking by platforms might explain why a regulatory approach was preferred, as it is meant to ensure some control over how platforms decide on removing illegal content. Yet, this outcome may have also been achieved by requiring compliance with the due diligence obligations for platforms to enjoy the liability exemption. In light of the changed role of service providers, particularly online platforms, the liability framework could have been developed further by linking the due diligence obligations to the liability exemption. This would have allowed for a move away from the passive/active distinction and would set a Union-wide liability standard for online platforms.

91

The new framework could also have focused more on achieving better, more precise and above all, more accountable and transparent automated tools for content moderation, rather than aiming to perfect notice and takedown systems. [185] Advances in machine learning technologies enable platforms to increasingly rely on automated tools to detect illegal activity online. The use of automated detection tools by hosting platforms should be encouraged, provided that important safeguards are in place. [186] Hopefully, online platforms will continue to advance machine learning technologies to reduce problems of over-blocking and allow illegal content to be removed swiftly and precisely.

92

The texts of the DSA and DMA have already been subject to extensive public consultation but still need to be approved by the European Parliament and the European Council. The importance of a liability regime for platforms and users suggests that these issues will still be the subject of thorough attention and lengthy debate at various stages of the adoption of the regulation.

Note: This article builds on Miriam C. Buiten, ‘Der Digital Services Act (DSA): Vertrautes Haftungsregime, neue Verpflichtungen’ [2021] Zeitschrift für Europarecht (EuZ) 102

*by Miriam C Buiten, Assistant Professor at the University of St. Gallen

[1] On the DMA, see eg Matthias Leistner, ‘The Commission’s vision for Europe’s digital future: proposals for the Data Governance Act, the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act—a critical primer’ [2021] Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (JIPLP) <https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpab054> accessed 31 May 2021; Damien Geradin, ‘The DMA proposal: Where do things stand?’ (The Platform Law Blog, 27 May 2021) <https://theplatformlaw.blog/2021/05/27/the-dma-proposal-where-do-things-stand/> accessed 31 May 2021; Andreas Heinemann and Giulia Mara Meier, ‘Der Digital Markets Act (DMA): Neues “Plattformrecht” für mehr Wettbewerb in der digitalen Wirtschaft’ [2021] Zeitschrift für Europarecht (EuZ) 86.

[2] European Commission, ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC’ COM (2020) 825 final (DSA), recital 56 preamble: “The way they design their services is generally optimised to benefit their often advertising-driven business models and can cause societal concerns”.

[3] See on the infringement of copyrights, trademarks, design rights and patents, eg OECD and European Union Intellectual Property Office, ‘Trends in Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods’ (Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing 2019) <https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9f533-en> accessed 5 May 2021.

[4] See European Commission, ‘Flash Eurobarometer 464 Report on Fake News and Online Disinformation’ (12 March 2018) <https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/final-results-eurobarometer-fake-news-and-online-disinformation> accessed 5 May 2021.

[5] Parliament and Council Directive 2019/790/EU of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC [2019] OJ L 130/92.

[6] Elisabeth Schulze, ‘Thousands Protest Against Controversial EU Internet Law Claiming It Will Enable Online Censorship’ (CNBC, 19 March 2019) <www.cnbc.com/2019/03/25/protesters-in-germany-say-new-eu-law-will-enable-online-censorship.html> accessed 28 April 2021; Morgan Meaker, ‘Inside the Giant German Protest Trying to Bring Down Article 13’ (Wired, 26 March 2019) <https://www.wired.co.uk/article/article-13-protests> accessed 28 April 2021.

[7] Christina Angelopoulos, ‘Harmonising Intermediary Copyright Liability in the EU: A Summary’ in Giancarlo Frosio (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Online Intermediary Liability (Oxford University Press 2020).

[8] See eg Miriam C. Buiten, Alexandre De Streel and Martin Peitz, ‘Rethinking Liability Rules for Online Hosting Platforms Rethinking Liability Rules for Online Hosting Platforms’ (2019) 27 International Journal of Law And Information Technology (IJLIT) 139; Natali Helberger and others, ‘The Information Society An International Journal Governing Online Platforms: From Contested to Cooperative Responsibility’ (2018) 34 The Information Society 1.

[9] Steve Stecklow, ‘Hatebook’ <https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/myanmar-facebook-hate/> accessed 28 April 2021; Alexandra Stevenson, ‘Facebook Admits It Was Used to Incite Violence in Myanmar’ The New York Times (New York, 6 November 2018) <www.nytimes.com/2018/11/06/technology/myanmar-facebook.html> accessed 28 April 2021; Olivia Solon, ‘Facebook Struggling to End Hate Speech in Myanmar Investigation Finds’ The Guardian (London, 16 August 2018) <www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/aug/15/facebook-myanmar-rohingya-hate-speech-investigation> accessed 28 April 2021; ‘Facebooks halbherziger Kampf gegen den Hass’ Der Spiegel (Hamburg, 16 August 2018) <www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/web/facebook-in-myanmar-halbherziger-kampf-gegen-den-hass-a-1223480.html> accessed 28 April 2021.

[10] Kate Conger and others, ‘Twitter and Facebook Lock Trump’s Accounts After Violence on Capitol Hill’ The New York Times (New York, 6 January 2021) <www.nytimes.com/2021/01/06/technology/capitol-twitter-facebook-trump.html> accessed 28 April 2021; Charlie Savage, ‘Trump Can’t Block Critiques From His Twitter Account, Appeals Court Rules’ The New York Times (New York, 9 July 2019) <www.nytimes.com/2019/07/09/us/politics/trump-twitter-first-amendment.html> accessed 28 April 2021; Ryan Browne, ‘Germany’s Merkel Hits Out a Twitter Over Problematic Trump Ban’ (CNBC, 11 January 2021) <www.cnbc.com/2021/01/11/germanys-merkel-hits-out-at-twitter-over-problematic-trump-ban.html> accessed 28 April 2021.

[11] The remainder of this article follows the terminology used in the DSA, which assigns a specific meaning to the term “online platform”. On the Typology of Online Platforms see further Jaani Riordan, The liability of internet intermediaries (Oxford University Press 2016).

[12] For an overview, see Buiten, De Streel and Peitz (n [8]) 139; Alexandre De Streel and Martin Husovec, ‘The e-commerce Directive as the cornerstone of the Internal Market: Assessment and options for reform’ (Study for the European Parliament, May 2020) <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/648797/IPOL_STU(2020)648797_EN.pdf> accessed 19 May 2021.

[13] European Commission, ‘Memorandum of understanding on the sale of counterfeit goods on the internet’ <https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/policy/intellectual-property/enforcement/memorandum-understanding-sale-counterfeit-goods-internet_en> accessed 12 May 2021.

[14] European Commission, ‘Alliance to better protect minors online’ <https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/alliance-better-protect-minors-online> accessed 12 May 2021.

[15] European Commission, ‘EU Internet Forum: Bringing together governments, Europol and technology companies to counter terrorist content and hate speech online’ (Press release IP/15/6243, 3 December 2015) <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_6243> accessed 12 May 2021.

[16] European Commission, ‘The EU Code of conduct on countering illegal hate speech online’ <https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/racism-and-xenophobia/eu-code-conduct-countering-illegal-hate-speech-online_en> accessed 18 May 2021.

[17] European Commission, ‘Code of Practice on Disinformation’ <https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/code-practice-disinformation> accessed 12 May 2021.

[19] Amazon, ‘Transparency’ <https://brandservices.amazon.com/transparency> accessed 28 April 2021.

[20] Google, ‘How Content ID Works’ <https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2797370?hl=en> accessed 28 April 2021.

[21] Zeba Siddiqui and others, ‘He Looked Like a Terrorist! How a Drive in Rural India ended in a Mob Attack and a Lynching’ (Reuters, 29 July 2018) <www.reuters.com/article/us-india-killings/he-looked-like-a-terrorist-how-a-drive-in-rural-india-ended-in-a-mob-attack-and-a-lynching-idUSKBN1KJ09R> accessed 28 April 2021; Donna Lu, ‘WhatsApp Restrictions Slow the Spread of Fake News, But Don’t Stop It’ (NewScientist, 27 September 2019) <www.newscientist.com/article/2217937-whatsapp-restrictions-slow-the-spread-of-fake-news-but-dont-stop-it/> accessed 28 April 2021.

[22] European Commission, Parliament, Council, Economic and Social Committee and Committee of the Regions, ‘Tackling illegal Content Online. Towards an enhanced responsibility of online platforms’ (Communication) COM (2017) 555 final.

[23] Commission Recommendation (EU) 2018/334 of 1 March 2018 on measures to effectively tackle illegal content online [2018] OJ L 63/50.

[24] Parliament and Council Directive 2011/93/EU of 13 December 2011 on combating the sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2004/68/JHA [2011] OJ L 335/1, art 25.

[25] Parliament and Council Directive 2017/541/EU of 15 March 2017 on combating terrorism and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA [2017] OJ L 88/6, art 21.

[26] Parliament and Council Directive 2018/1808/EU of 14 November 2018 amending Directive 2010/13/EU on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive) in view of changing market realities [2018] OJ L 303/69.

[27] Parliament and Council Directive 2019/790/EU of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC [2019] OJ L 130/92.

[28] Parliament and Council Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of June 20 2019 on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services [2019] OJ L 186/57.

[29] European Commission, ‘Accompanying the Document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Mid-Term Review on the implementation of the Digital Single Market Strategy A Connected Digital Single Market for All’ (Staff Working Document) SWD (2017) 155 final.

[30] European Commission, ‘A Union that strives for more: the first 100 days’ (Press release IP/20/403, 6 March 2020) <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_403> accessed 12 May 2021.

[31] European Parliament, ‘Report on the Digital Services Act and fundamental rights issues posed 2020/2022(INI)’ (A9-‚172/2020, 1 October 2020) <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2020-0172_EN.html> accessed 19 May 2021, para 24; European Parliament, ‘European Parliament, Resolution of 20 October 2020 with recommendations to the Commission on the Digital Services Act: Improving the functioning of the Single Market (2020/2018(INL))’ (P9_TA(2020)0272, 20 October 2020) <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0272_EN.html> accessed 19 May 2021, para 57.

[32] See further DSA, recital 2 preamble; European Parliament, Resolution (2020/2018(INL); European Parliament, ‘Resolution of 20 October 2020 with recommendations to the Commission on a Digital Services Act: adapting commercial and civil law rules for commercial entities operating online (2020/2019(INL))’ (P9_TA(2020)0273, 20 October 2020) <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0273_EN.html> accessed 20 May 2021; European Parliament, ‘Resolution of 20 October 2020 on the Digital Services Act and fundamental rights issues posed (2020/2022(INI))’ (P9_TA(2020)0274, 20 October 2020) <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0274_EN.html> accessed 19 May 2021.

[33] European Council, ‘Conclusions on shaping Europe’s digital future 8711/20’ (9 June 2020) <www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44389/st08711-en20.pdf> accessed 19 May 2021; European Council, ‘Special Meeting of the European Council (1 and 2 October 2021)’ (2 October 2020) <www.consilium.europa.eu/media/45910/021020-euco-final-conclusions.pdf> accessed 19 May 2021.

[34] DSA, 3 and 6.

[35] DSA, 5-6, see also recital 2 preamble.

[36] DSA, 8.

[37] The impact assessment points out that Art. 114 TFEU would probably not be appropriate as the internal market legal basis for harmonising the rules on tort law. European Commission, ‘Impact Assessment Accompanying the Document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC’ (Staff Working Document) SWD (2020) 348 final, Part 2 (Impact Assessment Part 2) 163.

[38] DSA, recital 17 preamble: The draft clarifies that the new rules should only specify “when the provider of intermediary services concerned cannot be held liable in relation to illegal content provided by the recipients of the service. Those rules should not be understood to provide a positive basis for establishing when a provider can be held liable, which is for the applicable rules of Union or national law to determine.”.

[39] See also Caroline Cauffman and Catalina Goanta, ‘A New Order: The Digital Services Act and Consumer Protection’ [2021] European Journal of Risk Regulation 1, 9. Rössel points out that the DSA hardly concretizes the liability rules, despite the Commission having identified the need for harmonization over the past years, because of the legal fragmentation of national bases for removal and cease-and-desist orders. See Markus Rössel, ‘Digital Services Act’ (2021) 52 Archiv für Presserecht (AfP) 93, 98 referring to European Commission, ‘Public Consultation on Procedures for Notifying and Acting on Illegal Content hosted by Online Intermediaries – Summary of Responses’ 3 Question 6 <https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=42071> accessed 30 August 2021.

[40] DSA, 12.

[41] European Commission, ‘Impact Assessment Accompanying the Document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC’ (Staff Working Document) SWD (2020) 348 final, Part 1 (Impact Assessment Part 1) 43, para 159.

[42] DSA, 12.

[43] DSA, recital 7 preamble.

[44] DSA, recitals 7-8 preamble.

[45] DSA, recital 12 preamble.

[46] DSA, recital 12 preamble.

[47] See further DSA, art 2(g).

[48] In this regard, Härting and Adamek question if each type of law violation warrants the obligations set out in the DSA. See Niko Härting and Max Valentin Adamek, ‘Digital Services Act – Ein Überblick. Neue Kompetenzen der EU-Kommission und hoher Umsetzungsaufwand für Unternehmen’ (2021) 37 Computer und Recht (CR) 165, 170.

[49] DSA, 10.

[50] Vice President of the European Commission Věra Jourová in September 2020, see Samuel Stolton, ‘Content removal unlikely to the part of the EU regulation on digital services, Jourova says’ (Euractiv, 23 September 2020) <www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/content-removal-unlikely-to-be-part-of-eu-regulation-on-digital-services-jourova-says/> accessed 5 May 2021.

[51] DSA, art 1(1).

[52] DSA, art 3: Mere conduit consists of the transmission in a communication network of information provided by a recipient of the service. The information is only stored automatically, intermediately and transiently for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission. As Polčák points out mere conduit providers essentially are defined as provider of communication links. See Radim Polčák, ‘The Legal Classification of ISPs. The Czech Perspective’ (2010) 1 Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and Electronic Commerce Law (JIPITEC) 172, 174. A typical example would be traditional internet access providers.

[53] DSA, art 4: Caching also consists of the transmission in a communication network of information provided by a recipient of the service. However, the information is stored automatically, intermediately and temporarily with the sole purpose of increasing efficiency. An example would be a “proxy server”.

[54] DSA, art 5: Hosting services include the unlimited storage of information provided by a recipient of the service. An example hereof are providers of webhosting.

[55] DSA, art 2(f); See further Gregor Schmid and Max Grewe, ‘Digital Services Act: Neues

“Grundgesetz für Onlinedienste”? Auswirkungen des Kommissionsentwurfs für die Digitalwirtschaft’ (2021) 24 MultiMedia und Recht (MMR) 279; Leistner (n [1]). On the implications of the DSA for non-hosting intermediaries, see Sebastian Felix Schwemer, Tobias Mahler and Håkon Styri, ‘Liability exemptions of non-hosting intermediaries: Sideshow in the Digital Services Act?’ (2021) 8 Oslo Law Review 4.

[56] DSA, recital 5 preamble and art 2(a) referring to Parliament and Council Directive (EU) of 9 September 2015 laying down a procedure for the provision of information in the field of technical regulations and of rules on Information Society services (codification) [2015] OJ L 241/1.

[57] Parliament and Council Directive 2015/1535/EU of 9 September laying down a procedure for the provision of information in the field of technical regulations and of rules on Information Society service (codification) [2015] OJ L 241/1, art 1-1(b).

[58] Parliament and Council Directive 2000/31/EC of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (Directive on electronic commerce) [2000] OJ L 178/1 (e-commerce Directive), art 1 and 2(a).

[59] Dessislava Savova, Andrei Mikes and Kelly Cannon, ‘The Proposal for an EU Digital Services Act: A closer look from a European and three national perspectives: France, UK and Germany’ (2021) 2 Computer Law Review International (Cri) 38, 40; Jorge Morais Carvalho, Francisco Arga e Lima and Martim Farinha, ‘Introduction to the Digital Services Act, Content Moderation and Consumer Protection’ (2021) 3 Revista de Direito e Tecnologia (RDTec) 71, 76.